It’s 2 o’clock on a Friday. We meet Matteo at the «Triennale di Milano» for coffee. The liveliness of the Italian coffee makes us sit closer. We talk about his thoughts, about different generations of architects and how time has influenced his work as an editor and curator of various magazines and exhibitions.

TT You curated the exhibition «10 architetture ital-iane» at this year’s «Triennale di Milano». What is it about?

MG The exhibition I co-curated with Enrico Molteni and Vittorio Pizzigoni showcases 10 projects built or under construction by Italian architects under the age of 35. In Italy it’s quite unusual that architects in their thirties have built projects, so it was difficult to find such offices. Each of them was asked to produce a model on a scale 1:5, a fragment of their project which becomes sort of a totem. In the exhibition room these totems look at each other, they talk about their differences and similarities.

TT What made it difficult for you to find these projects?

MG In Italy architects are young until their fifties. As the economic and political environment is quite rough, it’s hard to start your own prac-tice. The exhibited offices were able to build for various reasons. Some were lucky and got commissioned by private clients, others have won competitions and were able to plan public projects. In my opinion all these offices share an interesting personal feature: most of them show an extremely organized working method-ology. I don’t know, maybe that’s a character- istic of this new generation of architects.

TT Do you see any change in the architectural practice of your generation compared to these new architects?

MG Compared to us this younger generation is much more optimistic and takes everything they can. They take the classic «aunt’s bathroom» commis- sion and make the best possible bathroom out of it. There’s this positive approach and energy visible in their work. At the same time, they enter for a lot of competitions, even though they already have these small commissions. They place themselves in the discourse and make a statement. Neither do they push too hard on political issues, nor do they try to change society through their work. They try to make good architecture, with a good understanding of the subject, construction and materiality. It’s not that they don’t have their own agenda. They just take any chance to build and then they improve the initial conditions. I admire that approach. They have a certain positivity and a will to build as well as to discuss the built world instead of just ideas.

TT At the moment there is an intense discourse in our discipline about the need for change. How does this younger generation of architects react to this?

MG Maybe they are a bit disengaged. I think they might be tired of listening to discourses that have never turned out to be fruitful. Instead of focusing on peripheral discourses which have the tendency not to result in a clear architec-tural quality, they focus on the expertise of the architect. Maybe «disengaged» is the wrong word – another way to phrase it would be that they have a critical attitude towards the dis-course, generated around architecture, which is not affecting the built world. They admit that what they do is formal, so in that sense their work is honest.

TT Would you say there was a turn from the theo-retical to the practical?

MG There was once a tendency to avoid talking about architecture in itself. At IUAV, after Rossi, Valle and Gregotti came a period when none of our professors had realised any buildings. Theory didn’t meet practice. A lot of the offices exhibited here have a strong connection to Switzerland. Their architects either studied or taught there. They embrace this passion for the formal. They went back to a deeper construc- tive and architectural knowledge. I would criticize that «it feels like Switzerland» is the only reference for them. Swiss architecture has a kind of canon that is not suitable for Italy due to the structural, political and economic differences. In my opinion we should learn from countries that are more similar to Italy in terms of economy, politics and climate, like Portugal, Brazil or Mexico. Institutions in Italy usually don’t promote contemporary Italian architec- ture. To be able to change this you need to investigate what is happening. You have to go and search for projects and offices. In a panora- ma of exhibitions that cover only the big names of Milanese architecture, we simply tried to look at young offices and to understand what’s happening in Italy at the moment.

TT You are currently teaching in Genova. Where do you put the focus in your design studio?

MG I have been teaching the second and third year in Genova for 4 semesters. I try to involve these younger offices by inviting them to project reviews. I want the students to be closer to the people of this younger generation. They still have fresh memories of being at school and how they started their own practice, which can be of great value for people who just started their studies. When I started teaching I collaborated with Vittorio Pizzigoni who asked the students to recreate vanished or uncompleted works by Mies van der Rohe, in the first semester. In the second semester I proposed an exercise called «Miesunderstanding»: they had to study a project by Mies and change the context and program. There I realised that it was more meaningful to me to manipulate the work of someone else, than to start from scratch. Now we changed the topic and since then we have been working on «enclosures». This idea came from the first issue of the magazine «Rassegna», edited by Vittorio Gregotti, which was published in 1979 and had 77 issues. It was a monothematic magazine and the first issue dealt with the topic of enclosures – «recinti» in Italian. I was always quite fascinated by this topic. Defining limits is the first act of architecture.

TT What importance does the representation of architecture have in your work?

MG I work a lot with architectural drawings. Some years ago, for the magazine «Abitare» we pro-duced more than 200 pages of drawings which would explain the projects of others. Some-times our analysis went beyond the intentions of the author, simply because if you draw and redraw projects again and again, at some point they become your projects. Every architec-ture, once it is completed, is just out there and everyone can do with it whatever they want.

TT What about the covers of «San Rocco»?

MG We decided that we don’t want to have the title on the cover but to let a drawing speak for the content. We were looking at projects from different times in history which were all still contemporary in our eyes. To express their si- multaneous presence and the way they could talk to us today, we removed the authors and established a common rule of representation: the axonometric drawing. It’s a particular type of drawing; if you look at them they seem to be distorted, but when you measure them they are exact. I see them as objects laid out on one table so you can compare and discuss them.

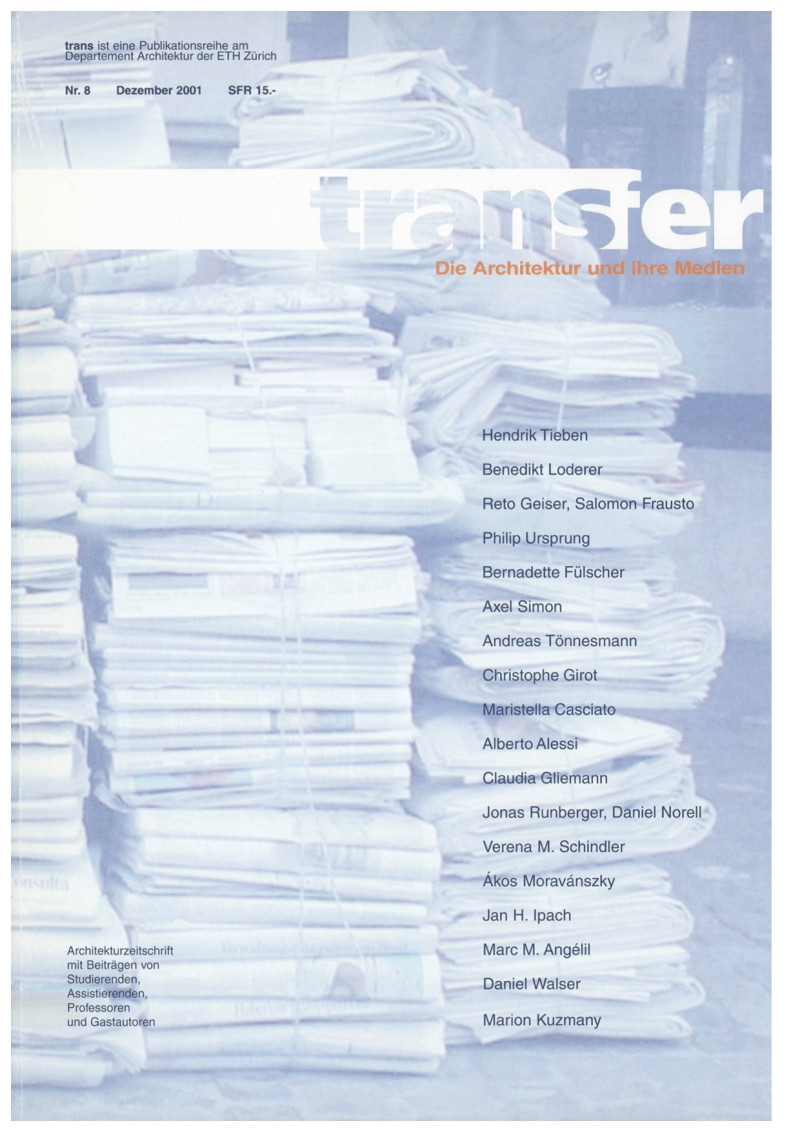

TT In your editorial of the first «San Rocco» issue you formulate a «five-year-plan». We are very interested in this idea of defining a precise time limit from the start. Could you tell us about how it came into being and what effect it had on the process?

MG Yes, in that way «San Rocco» relates to the topic of «time» quite evidently. There were a few reasons for the five-year-plan. First, we didn’t know if after five years we still wanted to do the magazine. It didn’t make sense for us to talk about a longer time span, because we knew that during five years a lot can change and we would be different in the end. Second, we started to think about «San Rocco» in 2008, two years before the first issue was released. 2008 was a moment of crisis for all kinds of projects – and especially magazines. It seemed as if every- thing would go digital. The paper production and printing industry was heavily affected by the economic crisis. We really wanted to do a print-ed magazine, even though it was basically the worst moment for doing that and we wondered how long this moment of crisis would last. Third, we felt a certain sense of responsibility. We said we are going to stop «San Rocco» after five years and want to publish 20 issues. Back then, we saw a lot of new magazines which disap-peared after the first issue was published. We didn’t want that. We wanted to establish a goal that could be reached. And last, in the end we had the feeling that we only have a limited amount of things to say and to express in this project. Besides, we noticed that a lot of magazines that we liked had a limited number of issues. The magazine I talked about before «Rassegna» would be an example. There are others: Terrazzo by Ettore Sottsass, or the amazing Pamphlet Architecture, just to mention a few. You need to finish a project to recognise it as one. We are all practising architects, we start a project, then we finish it and afterwards we can evaluate it. Maybe we transported this mindset into the «San Rocco» project.

TT We were fascinated by the fact that you knew you would «kill» the magazine from the be-ginning. trans magazin is working differently, the magazine continues but the editorial team changes constantly.

MG «San Rocco» started as a big collaborative pro- ject. When you are working together in a coop-erative environment, ideas and decisions are not based on yourself. If I had done the project on my own, maybe I would have continued.

But in such a big collaboration things happen – conditions change as well as relationships. If you look at it that way, five years is already a very long time for a project. In the case of San Rocco it even took more than five years to produce 16 issues. The intention was there from the beginning. During the meeting for the first editorial we decided all the themes we wanted to talk about. Of course, we didn’t follow the list exactly, some things changed within the process. But it’s good to make your decisions at the beginning in order to modify them later. In that way you stay aware of your changes. In the end we produced 16 issues and then we decided that’s enough.

TT How was it to work together in a large group?

MG We were all friends working in different offices. At an event by «Abitare» we first started to talk about the idea of doing our own magazine. We were all dissatisfied by what Italian mag- azines of that time were producing. They were talking about everything but architecture – about ecology, economy, society, politics and so on. Of course, it is important to talk about these issues, but why should architecture disappear completely? Architecture is a field of knowledge composed of many other fields of knowledge. But there is still something specific about architecture and you can put it in the centre of your discourse.

TT Why did you decide to be a monothematic magazine?

MG We knew from the beginning that we didn’t want to talk about new projects. We didn’t want to discuss novelty. We wanted to address the present, through talking about architecture of all times. We wanted to talk about topics that matter to us. There are many commercial magazines that want to be the first to publish a specific project. That was never our goal. In my opinion that’s quite pointless, because nowadays there are so many other medi- ums where a project is shown before being published in a magazine. I think you have to be able to formulate a critique based on the present. You can read an issue of «Casabella» from the 80s and find something which is still interesting today. Still they portray that specif- ic moment. Maybe the monothematic format allowed us to be more timeless. I hope some-body can read «San Rocco» in 20 years and still find it interesting and contemporary.

TT Could you tell us how you went from «San Rocco» to the «Book of Copies»?

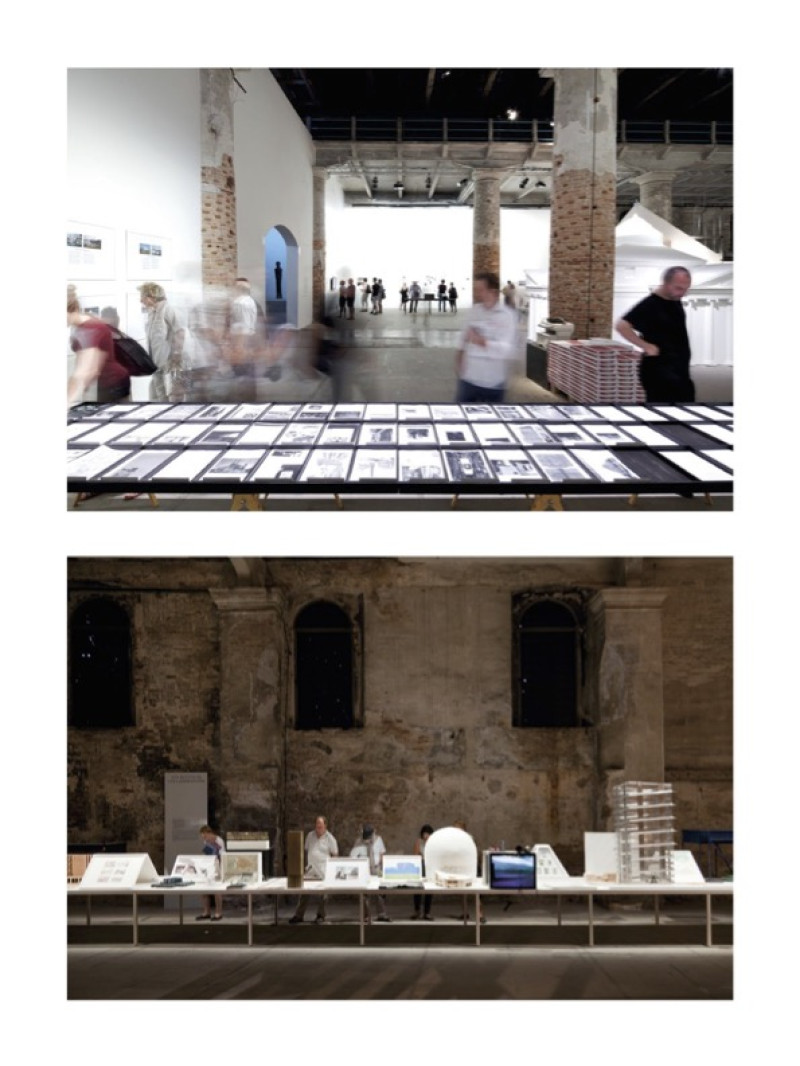

MG The «Book of Copies» is a project that had been in the air for some time. We found an occa- sion with the «Biennale Architettura 2012» curated by Chipperfield that was called «Com-mon Ground» to incorporate both projects.

«San Rocco» was invited to participate in the Biennale – which is quite unusual for an editorial board. The theme «Common Ground» was meaningful to us, so we accepted it. We presented a table of objects that we called «collaborations». For us this was a topic that mattered for the magazine as well as architec-ture, because they are both based on collab- orations. Time is an important issue, because we expressed that collaboration can happen between authors operating at the same time or in different times. We called them «synchronic» and «diachronic» collaborations. This second idea of diachronic collaborations is bound to the «Book of Copies». When you are saying that you are collaborating with the architects from the past – or the architecture of the past – we express it through the idea of copying some-thing that has been produced before. Architec-ture was always based on these types of acts without any problem, and the idea that copying is something embarrassing is quite new. At the same Biennale we were invited by Sam Jacob in his project that was called a «Museum of Copying» and there we presented the «Book of Copies». This collaboration project is again strongly linked to our generation. When we were studying, we used to make photocop-ies of the books. At that time, we didn't have the internet or Instagram and all those resourc-es. We would be photocopying the books. Since we did this in our studies and offices for ourselves, these practices were very common. They characterised our way of working. We invited other architects and artists to contribute with copies, suggesting that they could just do photocopies in black and white and also write some notes or draw on them. In the Biennale we had a big table that was divided into A4 modules. In each of them there was a pocket of photocopies produced by an author. One author with one topic. Then there was a photo-copy machine on the side and the people could make their own «Book of Copies». The idea for us in the end is that the knowledge of architecture is composed of every build-ing or project that has been built or designed throughout human time, and that anyone can use them to produce new architecture.

MATTEO GHIDONI

Matteo Ghidoni – architect – was a founding partner of the research agency Multiplicity from 2002 to 2006. He founded the architectural office Salottobuono in 2005. He has been a guest professor at the Università Iuva di Venezia, the Politecnico in Milan, the Royal Danish Academy of Arts in Copenhagen and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotà. Ghidoni is co-founder and editor in chief of «San Rocco», an independent international publication about architecture (www.sanrocco.info).

NOTES