«Been tryin' hard not to get in trouble, but I've got a war in my mind.»

Lana delRey, 2012, Ride. Born to Die

«For the commission to do a great building, I would have sold my soul like Faust. Now I had found my Mephistopheles. He seemed no less engaging than Goethe's.»

Albert Speer

Architects have the prerogative of designing the built environment. This comes with a responsibility; a political and social obligation that goes - or should go - beyond economic concerns. But are there any ethical limits to what architects design and for whom? Do architects have morals, defined as standards of behaviour or guiding principles of building what is right, or not building what is wrong? Legally, architects are liable for a number of tasks, such as contract completion, informing the client of inappropriate executions on site and of costs expenditure, etc. They also have the obligation to provide their services in good faith and to the best of their knowledge, in addition to a discretion and confidentiality duty. While these commitments constitute a legal framework in some countries, they do not include a moral code for our profession. Every architect is free within the limits of the law to work in any way he or she wishes to. In fact, architects design for brutal, dictatorial regimes, in doubtful security conditions, often claiming that architecture is detached from social, political and economical factors. Architects plan jails, concentration camps, detention facilities, weapon factories, gated communities, colonies; programs that have been ethically criticised for a number of reasons. Architects also participate in conceiving projects that are known to precipitate poverty and increase inequalities. Exploring examples of architects trespassing moral boundaries, this is an attempt to illuminate the ethics of the profession, questioning beyond political correctness its role in acting for the benefit of society at large.

The question of the social responsibility of architects has been recently addressed after the publication of a polemical article published in «The Guardian») about potential migrant workers deaths in Qatar and Zaha Hadid's quote: «It's not my duty as an architect to look at it.» Regardless of the accuracy of the data, an avalanche of responses followed, debating the moral liability of designers. Legally, an architect providing the sole design, or form to a project is not accountable for casualties on construction sites. While this point is questionable on moral grounds, safety on sites is only the visible tip of an architect's social responsibility, the fine balance between a successful business and society's welfare. The way offices operate internally is debatable as well. It is a known fact that many agencies have dubious work ethics, such as the common practices to hire graduated architects as interns or forcing employees into unpaid overtime. However, social responsibility is mainly about the kind of work an office is producing, how and where.

In fact, when operating in certain areas, the question of democracy and human rights, although easily dismissed on grounds of infamous «political correctness), ought to be of concern for offices working outside of their domestic realm. Politically, there is a social consensus on what is ethically acceptable and what is not. Viewed from the West, certain countries are considered <non grata>, for instance those ranking low in democracy standards among the 167 world nations: the pariah political regimes of Turkmenistan (160), Azerbaijan (148), and China (144). Such poor placing did not deter several Western architects from building in these countries. Working with the Turkish firm Polimeks, Arup participated in planning an Olympic village in Ashkhabad, capital of Turkmenistan (which is not to host any Olympic Games), together with British firm FaulknerBrowns Architects. Zaha Hadid Architects seems to have few concerns for the undemocratic situation of Azerbaijan, and the Hey- dar Aliyev cultural centre now stands in Baku. Similarly indifferent to human rights considerations, the large architectural firm HOK is involved in building towers in the centre of the capital. Authoritarian one-party state China is favoured with a large number of foreign architects involved in local construction: David Chipperfield, UNStudio, SOM, Coop Himmelb(l)au, OMA, to mention a few. This record suggests that many architectural practices do not consider democratic alarms as part of their concerns. The ¥$-system coined by Rem Koolhaas could be interpreted as to say that architects would not refuse any project as long as it pays. This is proven by many architects who have been working for brutal regimes, such as French architect Francois Barriere, and his mosque design in Baghdad for dictator Sadam Hussein in the late 1990s. Ateliers Lion Associés designed the Lycée Français in Damascus in 2005, under the authority of the French Foreign Affairs Ministry, at a time when doing business with the Al-Assad regime was still acceptable. Where are the limits of political neutrality? Asked provocatively, if one was to imagine that in a few years the terrorist group ISIS was to acquire a certain legitimacy, and was to launch an international architectural competition for a ministry complex or a center for slavery, would it be acceptable to enter it? Would Rem Koolhaas answer ¥$?

Such a provocative question points to concerns over architecture and some of its nasty programs such as jails, detention centres, concentration camps, weapon factories, illegal colonies, etc. The historical tracing of the birth of prison by Michel Foucault through the visionary work of Jeremy Bentham illuminated the repugnant ideology that lies behind the jailing of humans and their surveillance, a matter that is of no concern to many colleagues. In Switzerland, to name a few, Robert Moser (Lenzburg Jail), Bollhalder Eberle Architektur (Jail, St. Gallen), IPAS Architekten (Detention centre, Solothurn), Kunz und Mösch Architekten (Jail Muttenz, Basel), Dieter Jüngling und Andreas Hagmann (Jail Realta in Cazis, Chur) have designed detention centers and jails. Theo Hotz Partners won the competition for the Police and Justice detention centre in Zurich, still unbuilt. In the USA, there is a movement called «Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility.) The architects of the association refuse to participate in the design of spaces that violate human life and dignity, such as buildings designed for solitary confinement, torture, or cruel degrading, claiming this to be fundamentally incompatible with a professional practice that respects standards of decency and human rights. Probably far from such contemplations, it would be of value to uncover the architects and engineers behind the design of weapons factories. When reviewing the architects working for RUAG, the very respected state-owned Swiss firm that «specialises in high-quality pyrotechnic products for military small-calibre ammunition for armed forces and government agencies», the firm Halter AG and the architecture office Bauart Architekten, whose webpage ingeniously claims that «architecture starts with the people and seeks to serve society», have not collaborated to design and build factories but only the main offices of the Swiss weapon producer. Such cases disclose the political load of design and the «moral dilemma facing all architects».

While contextually distinctive, this moral dilemma is not radically different from the one faced by architects designing or partaking in projects known to be detrimental to poorer populations through gentrification. Architects and planners are vital agents to the process because of their role in renovating and constructing buildings in these urban areas.

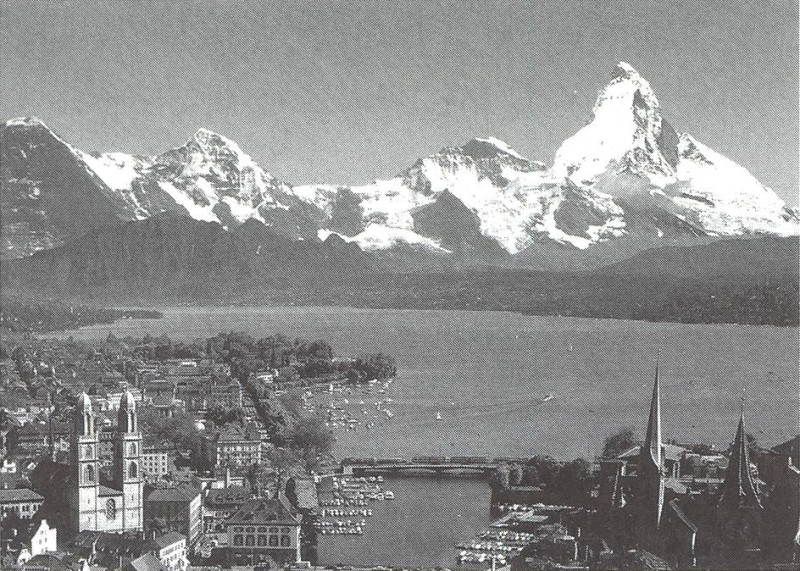

Contrary to what many architects claim, gentrification is not a process devoid from ideology. In fact, it is an economic scheme intending to financially reclaim the capital of urban space. The critical geographer Neil Brenner argues that gentrification, a phenomenon that first appeared in the cities dear to Saskia Sassen such as London, New York or Paris, is now a global phenomenon to be witnessed everywhere, symbolized by famous urban redevelopments led by prominent architects such as Potsdamer Platz in Berlin (Renzo Piano, Hans Kollhoff) or London's Canary Wharf (SOM, Norman Foster). The replacement of low-in- come inhabitants of a neighborhood with wealthier ones cannot be completed without the collaboration of architects, and those involved in such projects have clearly taken sides. In Zurich, the large-scale project Europaallee (David Chipperfield, Max Dudler, Gigon/Guyer, etc.) stands as a paragon of gentrification of the Main Station/Langstrasse area, with the infiltration of financial institutions and upscale housing units eventually leading to the destruction of the working class, immigrant, artsy avant-garde and political resistance lower habitat in Aussersihl.

To conclude, the question of ethics in architecture is not limited to the few aspects mentioned here. It concerns all architects, everywhere, and encompasses an even larger spectrum of dilemma including the type of materials used in construction, housing standards, environmental issues, etc. However, because architecture is inherently consuming resources that we know are finite, the final interrogation remains «to build or not to build»? Practitioners Lacaton- Vassal state that the first task of the architect is to think,and to decide whether to build or not. They have often stood against demolition (Tour Bois-le-Prêtre, Paris) or against building (Place Léon Aucoc, Bordeaux). This approach is close to that of French architect Patrick Bouchain (Grand Ensemble, Boulogne-Sur-Mer) or of Raumlabor, using informal networks, social space, and sustainable building processes. Among others, these architects are aware and morally attentive to the conditions in which their design is implemented and a building constructed, revealing the existence of ethics in architecture. Establishing our own guide of conduct, we practitioners must ask ourselves if building is always the right choice.

CHARLOTTE MALTERRE-BARTHES

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is an architect and an urban designer, a scholar, and an educator.

NOTES

(1) Lana del Rey, Ride. Born to Die - The Paradise Edition. Parker, Justin /Grant, Eliza - beth. Universal Music Group, 2012.

(2) In: Roger Forsgren, <The Architecture of Evil>, The New Atlantis, 2012.

(3) James Riach, <Zaha Hadid Defends Qatar World Cup Role Following Migrant Worker

Deaths>, The Guardian 2014.

(4) Rennie Jones, <Ban Vs. Schumacher: Should Architects Assume Social Responsibility?>, Archdaily (2014). http://www.archdaily.com/49085.... Reviewed: 4 Jan 2016.

(5) The Economist Intelligence Unit, <The Democracy Index 2011: Democracy under

Stress», 2011.

(6) Grand Designers - Faulknerbrowns, <Living North» (2012). http://www.livingnorth.com/nor....

(7) Zaha Hadid Architects, <Heydar Aliyev Center / Zaha Hadid Architects» Archdaily (2013). http://www.archdaily.com/44877.... Reviewed: 4 Jan 2016.

(8) HOK, «Igniting Baku's Reinvention»,2012. http://www.hok.com/design/type.... 9 Christopher Burns, <French Architect to Design Sadam's Gand Mosque», News Herald, 1 May 1998.

(10) Michel Foucault, «Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison» (Surveiller Et Punir), trans., Alan Sheridan,Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975/1979.

(11) Bundesamt für Statistik, «Der Vollzug Der Freiheitsstrafe: Der Wandel Der Gefäng¬

nisarchitektur», Kriminalität, Strafrecht 19,2015. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/

portal/de/index/themen/i9/o3/o5/dos/o3/o2.html.

(12) Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsability, «Ending Design for Torture and Killing,» 2015. http://adpsr.org/home/ethics_r....

(13) bauart, «Architecture and Sustainability» http://bauart.ch/competences-e..., accessed 4 Jan 2016.

(14) Alan Riding, «Are Politics Built into Architecture?,» The New York Times (2002). http://www.nytimes.com/2002/o8.... Reviewed: 4 jan 2015.

(15) See Neil Brenner and Nikolas Theodore, «Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe», Oxford: Blackwell.

(16) Lorenz Bürgi, «Gentrification Im Zürcher Langstrassenquartier Zwischen 1994-2014», Masterthese, Master of Advanced Studies in Real Estate, Zürich: Universität Zürich, 2014.