It is 11:54 in Beit Sahour, near Bethlehem. Sandi appears on the screen. She is wearing an elegant red necklace. A warm smile radiates her face. In the background we can hear the sound of the muezzin calling to prayer.

TM How did you begin your practice and how would you define DAAR?

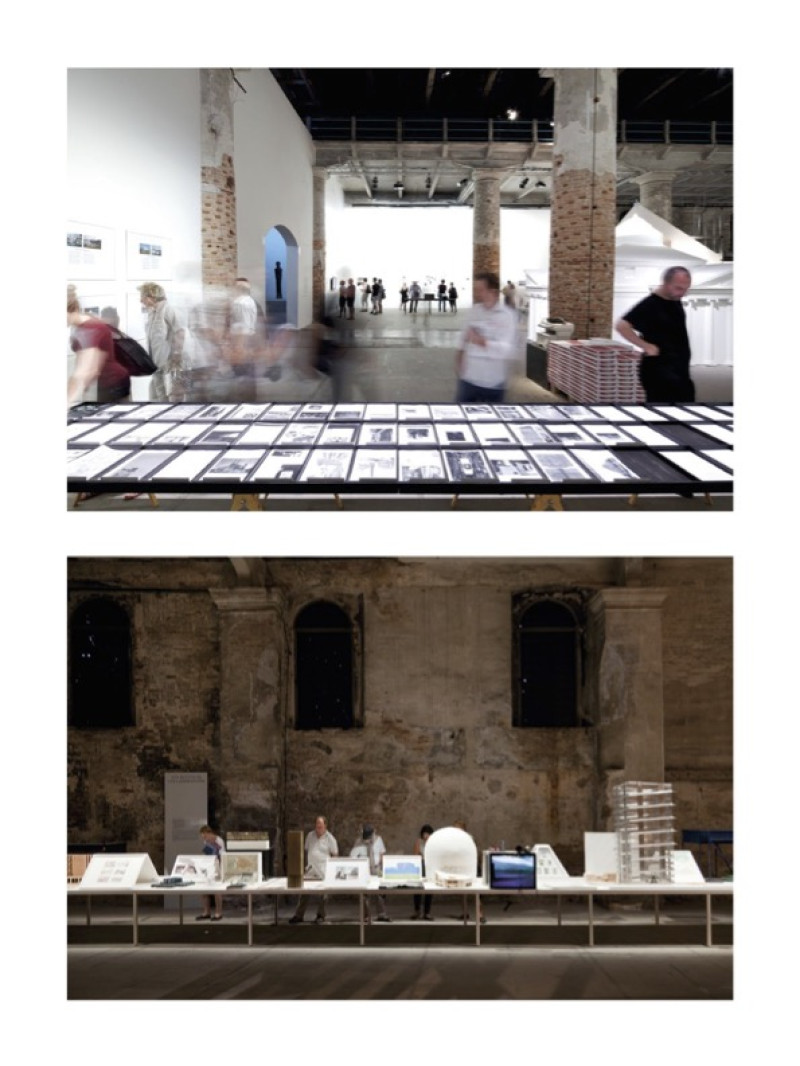

SH The first research project I did together with Alessandro Petti, my partner before DAAR, is entitled Stateless Nation and was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2003. The main point was how to highlight stateless people and to understand what it means. We used huge identity

documents for the Palestinian pavilion to claim that there are countless persons that still aren't represented, either by the state or by the architecture. At that time, we were specifically speaking to the West and desperate to outline this lack.

DAAR is Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency, but in Arabic, <dar> (jb) means home. We established it with Eyal Weizman in 2006, when Alessandro and I decided to move back to Palestine and our first daughter was born. We felt that at that moment it was a very important place for us from where to understand the world. An immediate shift happened: It was no longer about us convincing the West, but rather how we could function under colonialism and what it meant for us as a family.

In that sense, architecture wasn't only a job. With DAAR, there was no real separation between what is private and what is public. Our life was exposed from the moment we decided to understand what it means to live under those conditions. We opened up our house and ourselves to be able to start this discourse, which was lacking in terms of architecture and art in the public. We invited other scholars, architects, artists, and interested people, to understand colonialism today and how we could decolonize our minds and selves, in order to inspire others to do the same. Sometimes power structures are rooted in our heads and we don't distinguish anymore between our own narration and what has been imposed on us.

TM Would you call yourself an artist or an architect and what do you think is so crucial in the interrelation of the two?

SH I think that they both are equally important for us. As architects, we feel that we are constantly required to interact with social and political realities that can sometimes be extremely tough. When we began working in refugee camps in the West Bank, our main investigation was centered on the role of architecture in a place like refugee camps. If camps should not exist in the first place, then why should architecture intervene at all? How can we understand our role not only through the lenses of (helpers) and relief assistance?

To answer these and many other questions that were posed to us from the ground, exhibitions worked for us as a laboratory. We were dreamers moving constantly between reality and fiction. Art exhibitions were feeding the reality, and vice versa. It freed us from our limits and gave us the opportunity to allow others, especially the camp community, to dream with us, in order to bring those scenarios back into reality. I have the feeling that we, as practitioners, tend to forget the power of fiction.

Pedagogy is also very important in our practice, because whenever you want to involve people and work as a collective, you need to create a common language, in order to think and dream together. At a certain point, at (Campus in Camps», a university we established in Dhe- isheh Refugee camp, in Bethlehem, we felt the urgency to create a collective dictionary. It permitted us to grasp reality differently and to understand that colonialism is also very much about the imposition of language. We felt that maybe a way to decolonize our mind would be to redefine concepts that we use as if they had only one definition. Notions like (public), (private), (common), (mashà: «return to the common») and others need to be redetermined.

Therefore I would say that it is essential to use art, architecture and pedagogy together, in order to actually be able to speak about «decolonizing» architecture.

TM So basically you use art to decolonize the mind, the intangible, with the aim of then being able to decolonize the built, the physical, through architecture?

The combination was very important to be able to deal with reality and fiction simultaneously.

SH Steve Fagin, among the first persons that supported us, once said: «I feel that you are doing a sort of grounded Utopia.» I think that at the beginning it was an important part of our work. DAAR passed through different phases. We were intuitively learning and had to follow our own intuition and the thoughts we shared with others. We had few references to fall back on.

When we founded the practice, theory was an important concern. We developed scenarios on the possible appropriation of abandoned Israeli settlements and military camps, and what would happen the day after their liberation. We questioned the territory and challenged its reading.

Our research showed us, for instance, that those settlements were expropriated from Palestinians because they had collective forms of life, there are different types of collective forms of being together called <mashà>, which are owned by communities. People would come together and decide to cultivate a land around the village. The land would belong to them as long as they would activate it. Once they stopped, they would lose the right to it. This goes back to collectivity. In the West Bank, as one way of expropriation, Israel turned the collectivity into the public. Public means belonging

to the state, and the state meaning Israel.

So in that sense, we began to be suspicious about what <public> is. It was a major shift. Because after being a student in Venice, where it is all about how architecture can design great public spaces, and then realizing, that here it is a tool of expropriation, you begin to be

mistrustful of everything and to question the role of architecture.

Another one of those decisive moments occurred when we were in one of the halls at Ramallah municipality. We were looking at their map and saw white patches that they had decided not to plan. One was an Israeli colony. We were arguing with them, that if those settlements are within the borders of the Palestinian cities, then why wouldn't they give themselves the right to plan them, as planning would mean that you have ownership?

The other blanks on the map were refugee camps. It was an important statement from the

municipality to defend the right of return of refugees: «We don't touch the camp, as refugees should go back to their original homes». Those white spots opened up different questions, such as: What would happen to the camps afterwards? How would return practically take place? What would happen to the 70 years

of exile? What is the right of return, including both the right to history and the right of exile? How important is it to insist on the value of life in exile, as it might be one of the most crucial journeys of refugees' existence, which is disparaged only because it is a temporary period?

The research of DAAR was conducted in practically. Working on the ground we were faced with the condition of (permanent temporariness>. Living temporarily in refugee camps for more than 70 years: what does that imply and how can architecture treat such a contradiction in recalibrate our field of action. We are living in a world that is changing radically. Today, most of its citizens are more temporary than permanent, privileged persons and refugees alike. We have arrived at a moment where we can't understand what an interim architecture might be, if not a tent or a shelter constructed by Ikea. We tend to forget that for some people this temporariness might last forever. DAAR wants to challenge architecture, because as of now the only answer it offers to this situation is relief. It is giving an immediate shelter to persons who might well spend their whole future life there.

TM Do you think that your work is echoing the very precise context of Palestine, or could it extend to a wider horizon?

SH Actually, we just moved to Sweden last year, because for the first time we see the struggle of de-colonization inside the borders of Europe, where it's now essential and urgent to understand the conditions of permanent temporariness. Refugees and foreigners are often required to forget their roots, in order to be part of the new world, almost as an act of loyalty. We feel that the whole dis-course that we held in refugee camps is now essential here. That's our new challenge. We have developed a practice in Palestine over the last 15 years, and we now try to take it elsewhere. I'm currently doing a project called The Living Room in Boden, a former military town located in Northern Sweden, 80 kilometers from the arctic circle. From being a military town, it has now become one of the major reception centers for asylum seekers.

The first time I visited Boden, I was really without hope. Refugees would arrive and realize that what they found was not what they had dreamed of. They would find themselves in this dark place, thirty degrees below zero, in the middle of nowhere, and completely alone. A state of passiveness would set in, as if they had lost their political agency, which was so strong before. Projecting themselves elsewhere, they would blame the city as not being their final destination.

I was desperately looking for somebody who was planning to stay. To my surprise I found Yasmine and Ibrahim. I visited their house for the first time with members of the Swedish public art agency. The two young Syrian refugees received us with incredible warmth and hospitality. It felt almost surreal to me. The dynamic had been shifted. They were hosting the Swedish government in their tiny living room instead of accepting to be only hosted in their robes of eternal guests. In that sense, I believe, that architecture can perform an amazing function. Yasmine told me at a certain point, that what she loved about this project, was that her living room was the Syrian one brought to Sweden. It gave them agency. They were doing this very intuitively, without a strong intellectual apparatus, and then understood what it values on a theoretical level. You know, sometimes all you need is the ability to see certain things happening, name them, and underline the power they carry.

In Sweden, the public domain is highly codified, and as a foreigner you have to behave properly in order to be accepted. The problem is, that most of the people coming don't find their way into a sense of belonging, in the new public. Unfortunately, this leads to a society that is completely seg-regated. In that sense living rooms can become the place where collectivity occurs, where they use their own vocabulary, share it with others and create their own public space out of the private one. Nevertheless, it is only effective the moment they decide to open it not only among themselves but also to the Swedish society. This is where I see the living room playing a key role in the reciprocality of the relation between refugees and Swedes. It becomes a very interesting architectural transition, similar to what we saw in the refugee camps, where people are completely self-organized beyond categories such as private and public. There is no public administration managing the camp but at the same time people don't own the houses they inhabit. Exactly this space of transition can create a third place where refugees can regain their political subjectivity.

TM The story of The Living Room sounds very social and political. So hearing you talking, I would like to know: can we as architects react to this in a physical way?

SH Yes, absolutely.

At the moment there are five living rooms active simultaneously: The house of Yasmine and Ibrahim (1) and The Yellow House in Boden (2), the one in ArkDes Museum (3) as well as the one in Fawwar refugee camp (4), and finally my own living room in Stockholm (5). I would like to insist on the importance that these five spaces interact, inspire, and feed each other.

The scheme of Fawwar's refugee camp had a powerful impact on our work. The project

of The Roofless Square, in Fawwar was carried out ten years ago. At that time we were talking to the community about the kind of collective place they would need in the camp. They insisted on the requirement of a threshold as a possible spatial form that allows communal self-governance. Having no management or state taking care of the public space, they wanted to mark its entry, through a door, a wall, in order to give responsibility to the people getting in. This experience in Fawwar stayed with me as I moved to Sweden and as I was asked to do the living room project at ArkDes in Stockholm.

There, I decided to claim my political subjectivity as a foreign guest and my right

to host within my private space inside of the museum. We constructed a living room, with four walls and three doors similar to.the square in Fawwar. It is important to understand that this was not a representation but a real space. People would take off their shoes to get in. We would offer them hospitality, have tea together and share great discussions encouraged by the intimacy of the walls. The spatial conditions had changed and the social settings with it.

On the other hand, inspired by the living room of Yasmine and Ibrahim, we had a project in Boden involving a social building called The Yellow House, the kind of building with a mostly closed façade punctually opened by tiny little Windows, where asylum seekers live. The aim of the initiative was to create a diving room> shared by the inhabitants of the house and the people of the city. To do so, we used the existing ground floor and decided to destroy all the walls that weren't needed for the structure. It created a lot of openings. People got curious about the living rooms they were seeing from outside. The structure interacted with its users.

In that sense, for me, architecture works either by demolishing or building walls, but we have to realize that, by doing this, we form or

destroy certain collectivities. That's what interests me in this domain. We want to understand how we can mobilize social and political communities,

which tools to use to serve those who don't have access to architecture. And how can we make it meaningful? We need to get its essence and grasp it in its simplest form,

in order to engage with it and understand how influential it can really be.

TM How do you see the reality of the profession today and what do you think of the way it is taught in schools?

SH If there is anything that I would advise students, it's to be suspicious and dreamers at the same time.

I know it might be hard to question every single step, but architecture can become very dangerous, because you get your position from power. I mean, we are commissioned by elites, governments, sometimes regimes, colonial states, or even dictatorships. We accept it, thinking that we are only fulfilling a task. Maybe it's because we are living in an extreme condition of colonialism, that we were obliged to do so. However, it is just as essential in Europe.

It is also crucial to be wary towards our own desires. Of course it's nice to build a great piece of architecture. No one would say no, right? But then again, you have to ask yourself the right questions and never accept things as they are. I would say that in each project, our role as an architect changed. So in that sense, it is about understanding what our task is each time, about not being bound by only one way of proceeding.

Yet if we are suspicious, we should always believe in our ability to contribute to our own life and to the life of others. Sometimes when I visit Boden, I almost feel I am experiencing a fiction. Maybe because it's a landscape that is totally strange to me, as to any Syrian refugee actually. I feel completely out of place. Yet how to turn this being-out-of-place into a condition of potentiality requires from us not to give away our dreams.

SANDI HILAL

Sandi Hilal, born 1973, is an architect and researcher. She is the co-director of DAAR, an architectural office and an artistic residency program that combines conceptual speculations and architectural interventions (www.decolonizing.ps). Alongside research and practice, Hilal is engaged in critical pedagogy, she is the co-founder of Campus in Camps, an experimental educational program in Dheisheh refugee camp Bethlehem (www.campusincamps.ps). She headed the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) Camp Improvement Program in the West Bank (2008-2014).

NOTES

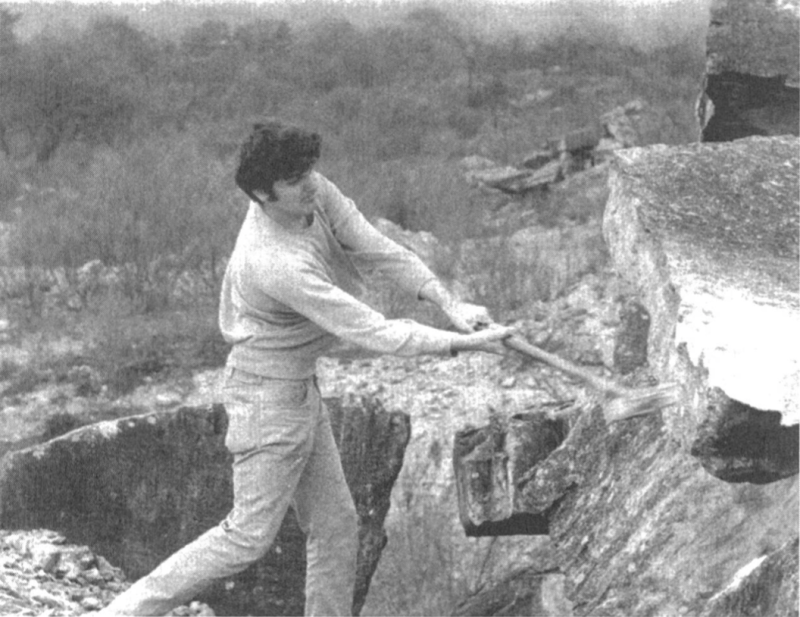

DaaR, ‹The Concrete Tent›, 2015. project made in the context of Campus in Camps. Dheisheh Camp, palestine. photograph: sara anna.