«How do we approach ‹complexities and contradictions in architecture› that are beyond the agency of the architect? In essence, how can architects and urbanists navigate what Bauman calls ‹Liquid Times› in an age of uncertainty?»

INTRODUCTION

For this interview essay I invoke the title of one of the most primal texts in architectural history, ‹Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture›(1) published in 1966 by Robert Venturi. In the book, Venturi presents a compelling critique to the modernism that preceded it. Critically examining ‹the revolutionary movement› that modernism was, Venturi calls into question the insufficient recognition that ‹orthodox modern architects› provided to complexity in their attempt to break with tradition and start all over again. Written in the backdrop of a period of unprecedented social upheaval of the 1960s, when social and political conservatism and colonial interventions were being challenged publicly, Venturi sought to question the modernist tendency of exclusion for expressive purposes, seeking to confront the idea of ‹less is more› with ‹more is not less›.

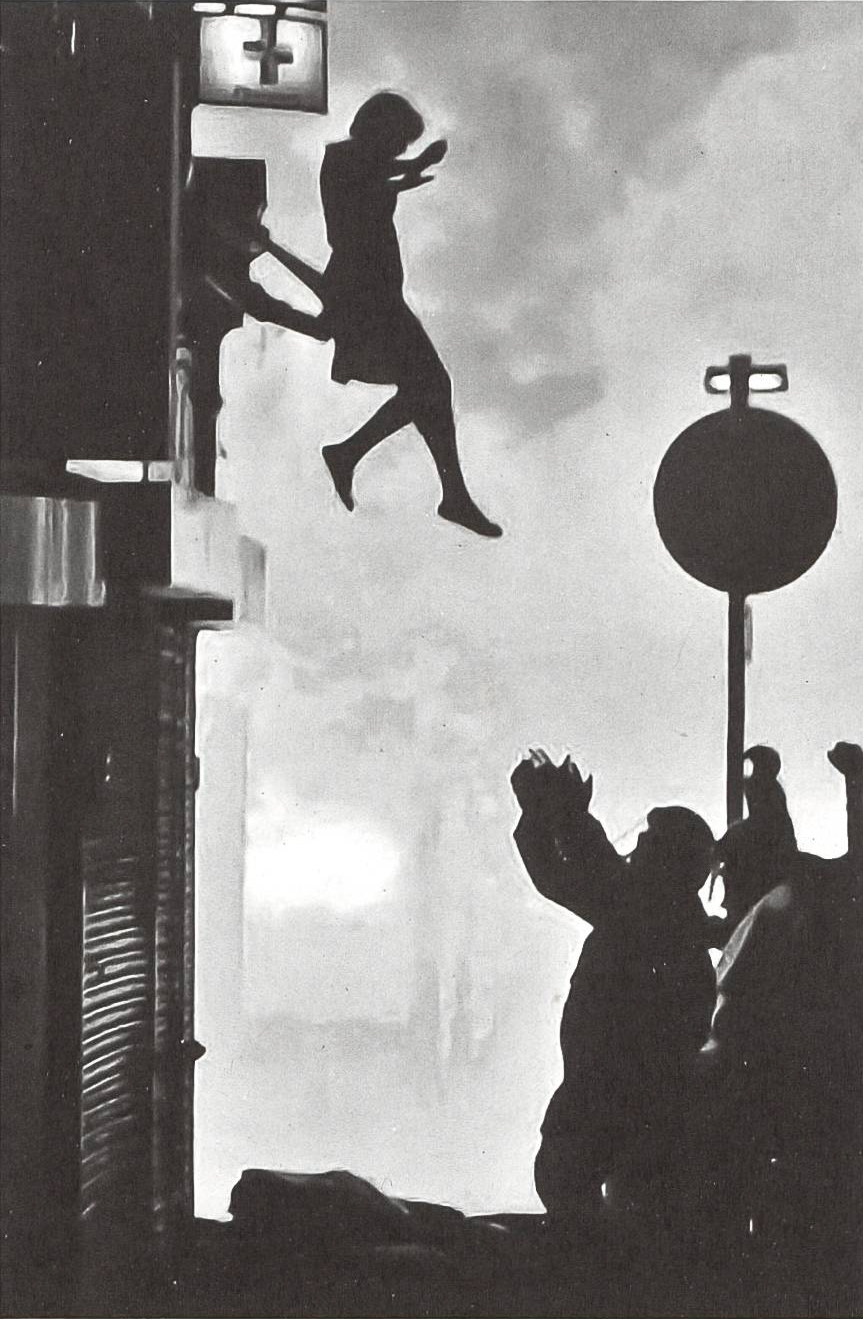

Using the book as a manifesto, Venturi sought to entangle architecture into a quandary of social and political complexities and contradictions. Resulting in a quagmire that has confronted interlocutors of architecture and urbanism with Postmodernity, Poststructuralism, and Postcolonialism.(2-5) A quandary that extends into the present, where complexities and contradictions have increased to such an extent that it is hard to separate fact from fiction, truth from lies, to a point when it finally feels that ‹the sun can lie›.(6)

How do we engage with architecture and urbanism in a world that is increasingly shrouded in tensions of transmuting forms of state violence? A world where architecture and urbanism features increasingly at the epicenter of humanitarian, ecological, and social conflicts. How do we approach ‹complexities and contradictions in architecture› that are beyond the agency of the architect? In essence, how can architects and urbanists navigate what Zygmunt Bauman(7) calls ‹Liquid Times› in an age of uncertainty? This is a specter that haunts many of us and certainly motivated my explorations in critical urban theory and architectural history as I wondered on how to operate in this Flatland(8) in a romance for many dimensions.

The work of Eyal Weizman and his collaborators at the multidisciplinary research agency Forensic Architecture has claimed to deal with some of the complexities discussed above. Starting with a critical examination of elastic strategies of Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories in the book Hollow Land, Weizman espouses the use of ‹forensics› to think and animate architecture socially and politically. Weizman has famously called space a ‹political plastic›(9), urging us to think of architecture not as dead matter, but rather as a vibrant materiality that resists in different ways and has its own agency. «When you come from that kind of understanding of materiality, ‹forensic› has another meaning. It is not the study of a dead body but of a living one coiling under pain.»(10) Along with Faiq Mari from GTA, I had an opportunity to pose some of these quagmires to Eyal Weizman through an interview. In this paper, I combine the interview excerpts with an analysis of Weizman's writings to engage with an elastic world through ‹complexities and contradictions in Forensic Architecture›.

I. POLITICAL PLASTIC IN AN ELASTIC WORLD

Complexities and contradictions in Architecture for Venturi were about tensions and paradoxes between «what a thing wants to be» and «what the architect wants things to be». Venturi operationalizes architectural history to read and isolate such ‹tensions› in buildings. Through shifting agency from the architect to architecture or even more banal, to buildings and built environment so to say, Weizman propels architecture into yet more ‹complexities and contradictions› namely those of Forensics. Thus offering not only ways of understanding architecture and urbanism, but also of employing tensions and paradoxes for social and political action.

«An architecture historian would no longer disregard politics and autonomy in their work as you need to understand the building as a product of a certain ideology and means of economic production. However, the difference between ‹forensic architecture and architecture history› is in our role as historians. The foundation of architecture history is to see the world as interpreted in the brain of an architect, which comes out as a line and becomes architecture. I think that, if you shift the framework from the architect to the building, something else happens. The building itself as a piece of materiality is the medium that synthesizes ‹contradicting› political forces, the architect just being one of them.»(11)

This breaking down and blurring of barriers, distinctions, and hierarchy between the ordinary and the spectacular, architect and social actors, politics and aesthetics, death and life has major political implications. Compelling architecture to become the subject of what is known as an object oriented or flat ontology(12-13) allowing meaning to be made from any building regardless of its location, features, use, inhabitants, or architect. This stands in contrast to the ‹gestalt psychology› approach of making meaning of the whole from building parts that Venturi and the many who have followed him have embraced.

In a world of conflicts, this ‹flat approach› allows us to appreciate and address architecture and politics in places spread far apart such as Zurich and Mumbai, Palestine and Kashmir with the same rigor. Thus, liberating us from the shackles of colonial vestiges such as center-periphery, developed-developing, north-south and so on. This is well illustrated in the work of Forensic Architecture, which approaches cases such as the ‹shooting of Mark Duggan in North London› with the same rigor as it does investigating a ‹factory fire in Karachi, Pakistan›. This ‹contradiction in Forensic Architecture› allows architects to gain agency in confronting state violence through loosing agency in the shift of political analysis from the architect to the building.

II. WRITING IN AN ELASTIC WORLD

Through his prolific writings, Weizman tempts us to transcend the thresholds of architecture thinking in an increasingly uncertain and liquid world. While in Hollow Land he lays threadbare the architecture of the Israeli occupation in Palestine(14), in the succeeding books he tests the possibilities and limits in such counter-scholarship. In ‹The least of all possible evils›(15), he problematizes the role of humanitarian agents in fueling and maintaining conflict. While in ‹Megele's Skull›(16), he attempts to survey the advent of the ‹Forensic Aesthetic›, the science of speaking for objects. The book, for Weizman thus becomes a treatise, not only for self-introspection, but also of exploring possible ways of intervening in the ‹fluid times›.

«Forensic architecture emerges in ‹The Least ofAll Possible Evils›, as an introspection of myself, because after writing ‹Hollow Land› I realize that there is one more actor in the soup. How the very Forensic methods of understanding how buildings are destroyed are based on the very technologies that have been conceived to do it. Such as, how do the trials against the wall end up supporting the wall? This humanitarian actor that exists in-between is maybe not that innocent.»(11)

Weizman's books thus alternate between being ‹probative and decisive›, bringing into question the role of technologies and actors in an uncertain world while simultaneously finding ways of operating within it. This elastic auto-critique, what Weizman calls «finding a compass» serves as another contradiction in ‹forensic architecture›, one that allows the book to simultaneously exist both as a personal treatise and a manifesto. Thus allowing to expand and invent new forums and enhancing the possibility for ameliorative action.

«Auto-critique is what allows you to operate autonomously, if you do not wish to be apart of a big political party. Therefore, what I do in the book is to think through the conditions that I want to pursue and I will always choose the next book to be what is that I need in order to operate in the world. So sometimes it is going in all directions and sometimes it is a bit more focused.»(11)

III. CONTRADICTIONS OF COUNTER-CARTOGRAPHY AND ALTERNATIVE FORUMS

Following Edward Said(14) Weizman operationalizes counter-cartography to understand not only the facts on the ground, but also how they are charged with and dispense power in the world.(11) Such retooling to combat power structures offers a ‹counter-apparatus›, opening possibilities for ‹decolonizing architecture›.(17) This idea of ‹counter-cartography› in forensic architecture however gradually morphs into ‹counter-forensics› in exploration of forums where the products of the ‹counter-apparatus› could be presented. This duality of operating the ‹counter-apparatus› simultaneously as a way of seeing and practicing is another ‹contradiction› that forensic architecture employs in order to operate in the ‹fluid times›.

«Counter-forensics has two dimensions to it that are always entangled. First is that of a clarification of what is happening, the easy part. The difficult part however is to undo. Counter-forensics is about going against the pronouncement. So you do not just say what happened, you show how the state investigation of a particular crime is produced in a way that uses the ideology of the state in order to either cover up, or, for different reasons manipulate the evidence.»(11)

In order to expose and deconstruct the ‹ideology of the state›,forensic architecture employs ‹contradictions› between the diverse forums it operates. At the time of this interview, a report on the violent police shooting of Mark Duggan, a 29-year-old man was just released by Forensic Architecture agency(18). In 2011, the shooting sparked the biggest riots in modern British history, and prompted the police to cover-up the evidence against it. Forensic Architecture not only helped unmask the cover-up, but also employed ‹tensions› between the different forums allowing productive opportunities to challenge, expose, and reform them.

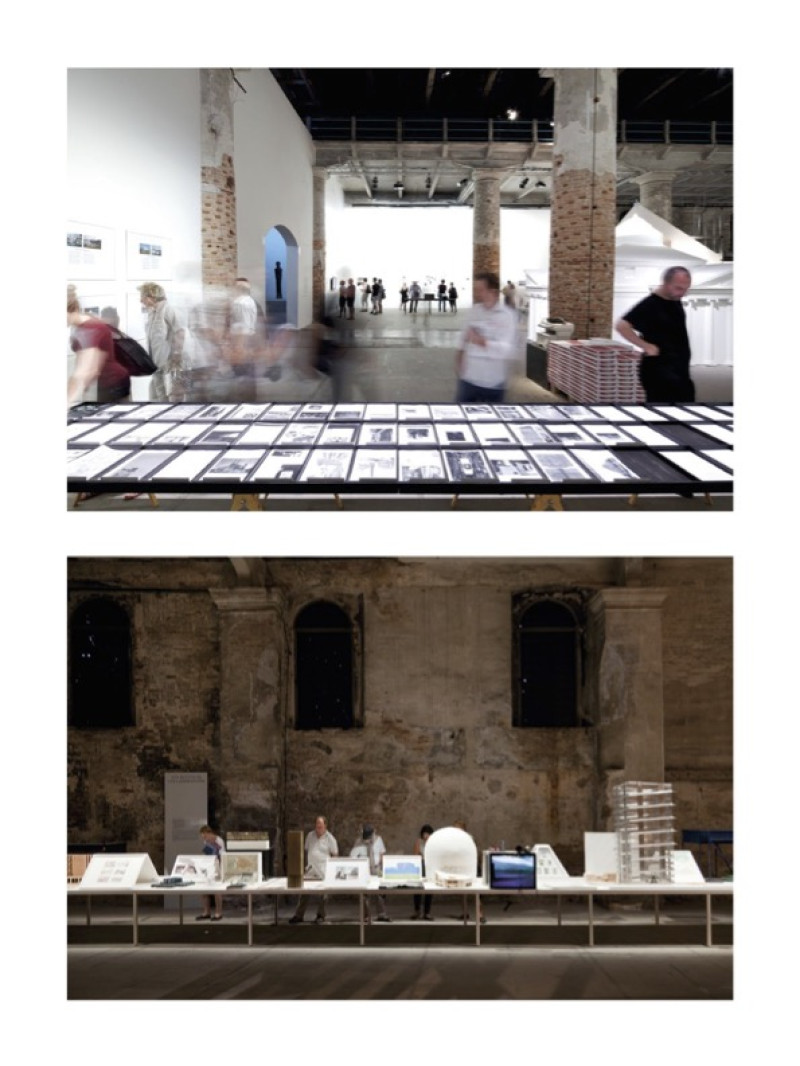

«We did not go to court or to the media, but rather to the community in Tottenham, North London, and we presented the findings to the family of Mark Duggan in front of a full house of people that came to listen to the facts. There were journalists present there that have now reported on it, but our first approach was to find a forum that is an alternative to the court. Now this hopefully will influence the legal process backwards. Today in my conversation with the Mayor of London over the radio, I said, are you going to effectively instruct or ask the official investigation to be reopened, based on the investigation?»(11)

This contradiction of not approaching the court of law directly but opening it through mobilizing alternative forums such as the public of Tottenham allows forensic architecture to operate fluidly, thus highlighting another important ‹contradiction in Forensic Architecture›.

IV. ARCHITECTURE OF COMPLEXITY AND CONTRADICTION IN A POST-TRUTH WORLD

Writing about ‹the obligation toward a difficult whole›, Venturi describes how an architecture of complexity and accommodation does not forsake the whole because the whole is difficult to achieve. He writes: «But an architecture of complexity and contradiction also embraces the «difficult» numbers of parts — the duality, and the medium degrees of multiplicity.»®

We are increasingly confronted not only with a deluge of information that fills the public fora, but also with even fewer ways of verifying them. In response, institutions and communities of all shapes and sizes have emerged over the internet that claim to counter and produce ‹alternative narratives›. Often times, it is hard not only to ascertain the validity of evidence from counter evidence, but also whether these communities serve ulterior purposes. How to navigate such complexities, such ‹dualities› where it is hard to ascertain even basic truths. In a recent article, Weizman calls this duality a ‹dark epistemology›(19), and rather than shying away from it he proposes for thoughtfully maneuvering it through the principle of ‹open verification› allowing for hundreds not thousands of public records to be corroborated.

«We are like the post-truthers, because we say do not trust the police, the secret service, the courts and the government experts, because we counter investigate them... On the ruins of institution-based traditional epistemology, on the power-knowledge centers, those big pillars on which our society rests, we need to build something new. So my attempt is to build an ethical, political, technical, epistemological structure on the ruins and the dust of images and of cities.»(11)

Weizman embraces and exploits these dualities in a ‹architecture of complexity and contradiction› in order to resolve them into a productive new beginning rather than to suppress them.

V. CONTRADICTIONS OF AESTHETICS

The development of forensic architecture has also been witness to a systematization of aesthetic production. This aesthetic usually involves the spatial navigation of crime scene set within ‹dynamic digital environments› where evidentiary materials such as photos, videos, audio recordings, and witness testimony are brought together by narrations that explain the sources and assembly process. This, Weizman claims, makes these video investigations a ‹how-to› allowing the «public domain to function in analogously to scientific peer-review.»(19)

«Forensics is not simply about science but also about the presentation of scientific findings, about science as an art of persuasion. Derived from the Latin forensis, the word's root refers to the «forum» and thus to the practice and skill of making an argument before a professional, political, or legal gathering.»(16)

Weizman's analysis of aesthetic production as a tool for public persuasion in the legal examinations of Mengele's Skull, has been key to this insistence on systematic aesthetics. Weizman claims that this systematization allows for the emergence of an ‹aesthetic commons›that can help counter post-truth regimes. Furthermore, he claims, the systemization can simultaneously allow ‹open-source› evidence to get on par as ‹traditional forms› of evidence, while closing the gulf between science and art, thus allowing ‹contingent, collective, and poly-perspectival accounts› to come together.(19)

The insistence on a virtual hyper-reality in forensic architecture however poses another contradiction about the autonomy with which public(s) can engage and relate to such ‹aesthetic commons›. «It is a powerful first punch into the world, although indeed we are experimenting with different forms». It is in this spirit of experimentation that I would like to bring the ‹forensic architecture aesthetic› in conversation with the wanderings of the visual anthropologist Michael Taussig.

Taussig, in his now classic text ‹I swear, I saw this›(20), examines the use of drawing and photography in ethnographic research, museums, and courts. He raises the paradox of «why is the drawing okay but not a photograph? For certainly the photograph of the drawing is not only okay but very awful... the courtroom being a place where people swear to tell the truth and where photography but not drawing is prohibited.» While Taussig does not offer conclusive answers to the questions he poses, he offers the following observation, which can help expand the idea of (aesthetic commons):

«...drawings come across as fragments that are suggestive of a world beyond, a world that does not have to be explicitly recorded and is in fact all the more ‹complete› because it cannot be completed. In pointing away from the real, they capture something invisible and auratic that makes the thing depicted worth depicting.»

VI. SO IS FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE CONTRADICTIONS OF AESTHETICS AN EPISTEMOLOGY?

Traditionally, epistemologies have provided us ways to know, to understand, and to be acquainted with the world. Can forensic architecture offer ways of working and operating in the world for others wanting to understand the world around them? Weizman offers us another paradox here:

«It is complicated! We definitely start building an epistemology. But my fear is of it becoming a discipline, because a discipline is a prison. It is a mode of thinking and conceptualizing a problem, between the political the judicial, if you like, the scientific and the aesthetic. It moves between institution of aesthetic production, institution of science, the university, institution of law, and of art. And, that is its power, the fact that you cannot really capture us. You want to say, oh, these are artists! We go show an exhibition, and they say —No, these are scientists! We kind of like ducking and diving! And trying not be imprisoned by any one of those.»(11)

Forensic architecture then offers a liquid epistemology, a way of operating in liquid times as Bauman(7) describes it. An epistemology that operationalizes contradictions in order to operate in the world. An epistemology that is a contradiction in itself, ‹the last and yet the most lasting contradiction in Forensic Architecture›.

«What I see in a sea of elasticity that surrounds me, are forces a little bit like in a flat ontology kind of fighting it out. The place of the planner is not divided from the space of the resistance fighter who influences space in a same way. If you let space liquefy, you allow for small forces to be geared up.»(11)

Instead of offering a formula, Weizman offers some principles for those looking to tread the thin line between academics, professional practice, and activism:

«First, we do not produce evidence in a vacuum, it needs to be with a group that can benefit from a particular evidence. Second, the production of evidence is not simply about improving military domination practices but resisting or showing the impossibility of their acceptance. Third, the mechanism of production of evidence builds a second community of practice with people on the ground. The actual process of investigation is a process of community building.»

VII. CLOSING WORDS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This ‹tension› between the ‹whole› and ‹parts›, the rapid alteration between ‹gestalt theory› and ‹flat ontology› in forensic architecture allows productive contradictions for operating fluidly in a world marred by tensions. Some of the inherent ‹complexities and contradictions in Forensic Architecture› that I have identified here such as fluid epistemology allow architecture to gain agency as a ‹political plastic› whose forces can be liberated for political and social action.

I would like to thank Faiq Mari from GTA for his help with the interviews, finding and reviewing literature and critical feedbacks to early drafts of this text. I would also like to thank the fellow participants in the course on ‹Advanced Topics in History and Theory of Architecture› at DARCH, ETH especially Metaxia Markaki, David Kostenwein, Nicole La Hausse De Lalouviere, and Ina Valkanova for the critical comments they raised during the seminar.

NITIN BATHLA

Nitin Bathla is an architect, artist, researcher and educator based at ETH Zurich where he is currently pursuing his Doctoral Studies. Nitin's work focuses on labor migration, and land ecology in the extended urban region of Delhi. Aside from academic writing, Nitin works on filmmaking and community art projects.

NOTES

(1) R. Venturi, Complexity and contradiction in architecture, vol. 1. Garden City-N.Y: Doubleday, 1966.

(2) F. Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The cultural logic of late capitalism. London: Verso, 1991.

(3) J. M. Jacobs, Edge of empire postcolonialism and the city. London: Routledge, 1996.

(4) J. Jacobs, The death and life of great American cities, vol. 241. New York: Random House, 1961.

(5) R. Venturi, D. Scott Brown, and S. Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas. Cambdrige-Mass: MIT Press, 1972.

(6) Susan Schuppli, «Can the Sun Lie?» in Forensis: the architecture of public truth, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014, pp. 56-64.

(7) Z. Bauman, Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty, 1 edition. Cambridge: Polity, 2006.

(8) E. A. Abbott, Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions.: A Fantastic Story of Humours (Annotated) By Edwin Abott Abott.Independently published, 1884.

(9) E. Weizman, Hollow land: Israel's architecture of occupation.

London: Verso, 2007.

(10) E. Weizman and A. Herscher, «Conversation: Architecture, Violence, Evidence», Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 111 -123, 2011, doi: 10.5749/futuante.8.1.0111.

(11) «Interview with Eyal Weizman», 03-Dec-2019.

(12) M. DeLanda, Assemblage Theory, 1 edition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

(13) L. R. Bryant, The Democracy of Objects: Open Humanités Press,2011.

(14) E. W. Said, Culture and Imperialism. Vintage, 1994.

(15) E. Weizman, The least of all possible evils: humanitarian violence from Arendt to Gaza. London: Verso, 2012.

(16) T. Keenan and E. Weizman, Mengele's Skull: The Advent of a Forensic Aesthetics. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012.

(17) A. Petti, S. Hilal, E. Weizman, and Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency, Architecture after revolution. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013.

(18) V. Dodd, «Mark Duggan shooting report challenged by human rights groups», The Guardian, London, 05-Dec-2019.

(19) Eyal Weizman, «Open Verification», Becoming Digital-Eyal Weizman-Open Verification, 18-Jun-2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.e-flux.com/archite....

(20) M. T. Taussig, I swear I saw this: drawings in fieldwork notebooks, namely my own. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2011.