The conversation took place in Hélène Binet's home and studio in Kentish Town, London, and was held and recored by Sören Davy, Ferdinand Pappenheim (in absentia), Elizaveta Radi and Linda Stagni.

After a productive morning of work in the lobby of the Hoxton Holborn hotel in central London, the trans editors venture north to meet Hélène Binet at her home and studio in Kentish Town. We enter through a narrow passage, overgrown with greenery, to be greeted at the door that leads up to her studio. She is busy developing the last films from her recent trip to Belgium, before we join her in her home on the next floor. We are surrounded by bookshelves that loosely define rooms within the loft-like space, filled with an abundance of personal and ethnic objects. She carefully places a plate of fruit before us, smiles, and invites us to talk about our magazine, curation, and her work.

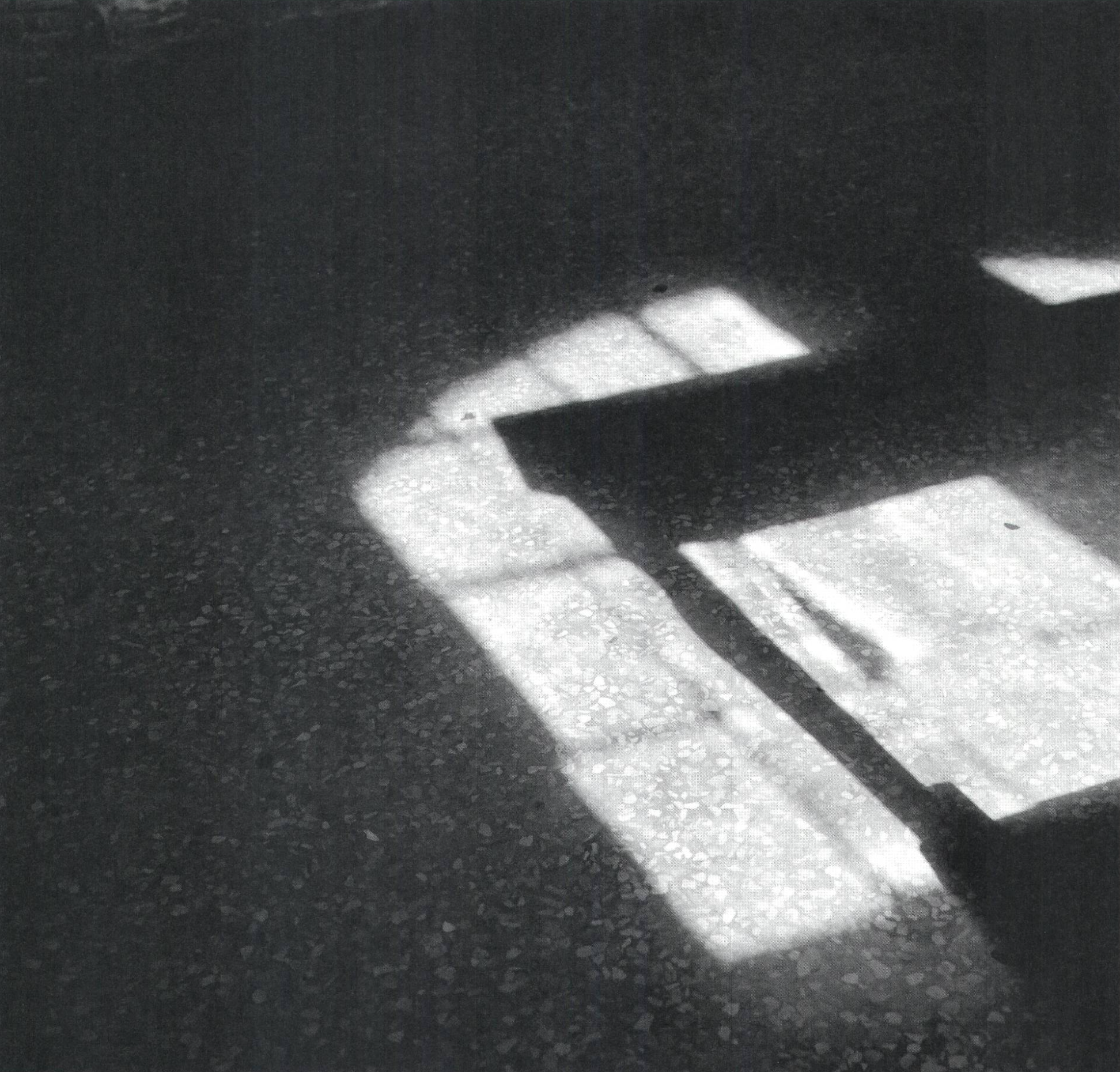

Trans Magazin (tm): Your work focuses on aspects of light in space and on material surfaces. By carefully selecting and photographing these fleeting moments, one could say you <curate> a mental image of a building: You piece together a very specific atmosphere and try to offer a unique reading of the architecture.

How strongly does this relate to the act of curating?

Hélène Binet (hb): The act of photography is an act of choice. 1 am not an artist that makes objects; I have everything around me. In the act of photography we say <yes>; we select and exclude. So there is no way of making an image without making a curatorial choice. When and how, which lens, what time of the day, how close—this is the beauty of it, in my opinion. The world is just there, and saying <yes> is a confirmation that something exists now, and has a value now, and I like it now, and I want to represent it now. This goes back to the medium that I use, film. I like this kind of relationship, the moving of the world around us and this act of saying <yes, now!>.

How I do it and what the parameters are depends on the condition of the world, the architect or what my circumstances are, in a specific context. Of course in the best of cases, the ones I would create for myself and sometimes get commissioned for, I am inside architecture and I look for something specific. Because architecture is an intricate experience we perceive with all our senses, and in many different ways, the act of selection is complex. You have to have very precise parameters to say <now I am looking for that». It is beautiful when you are in a space and you start to focus on a very specific condition, instead of taking whatever comes your way. You are filtering, not only looking but also thinking of how to frame. Framing is an incredible tool. You can really change the way you communicate by the way you frame.

tm: We have tried to define curation without it being too museological, as a form of production, by combining existing information. This is what we saw in your photography...

hb: ...the pairing...

tm: ...exactly, the pairing. Are those <pairs> moments you decide to combine and look for while photographing a building or does this take place in postproduction?

hb: It's a combination. I have realized for a long time that it is impossible to convey an entire spatial experience. I have adopted this process of reduction, of using black and white and of recording details. I like to reveal something. I think about how one subject would look or interact with something else. We can create spaces with our mind, like when we dream or read a book; we make spaces that are unique. I have devices that I believe can make an observer create his own space. Pairing is one of them. At times I like to combine geometries, at other times certain elements might be similar. You start to associate them and wonder what they might be or if they belong? This doubt, this playing with what you see allows you to create this space.

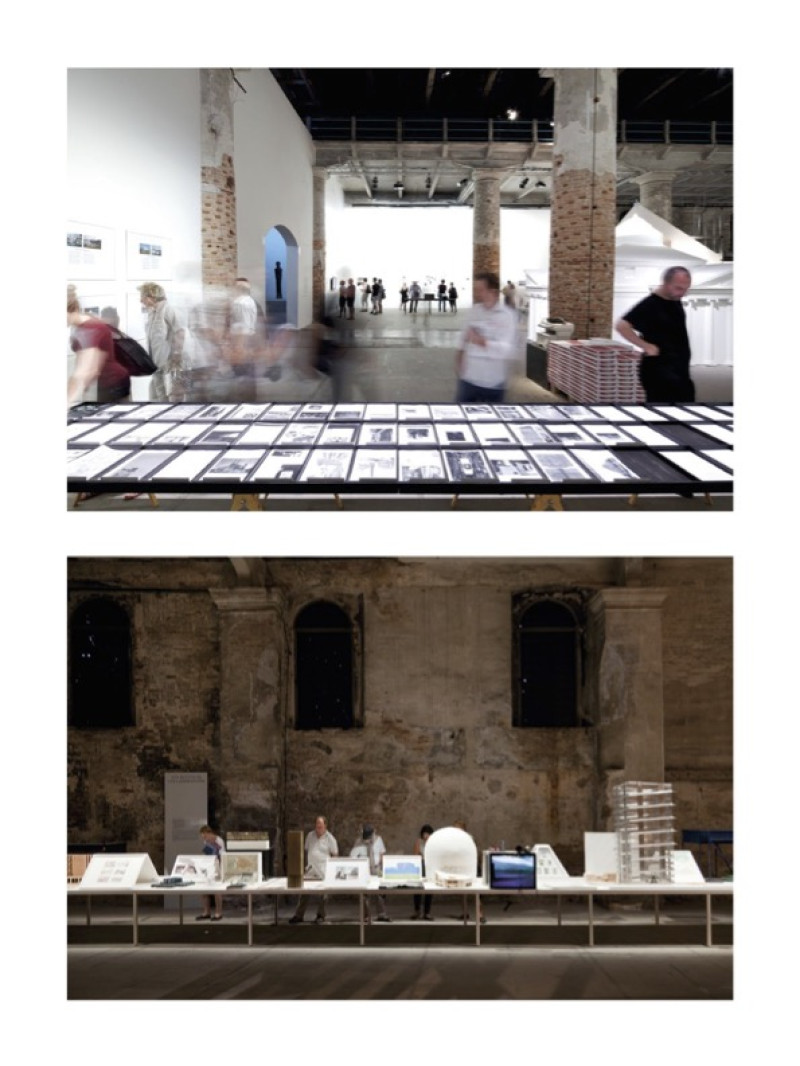

Sometimes I look for pairs while taking photographs It would be hard to find pairs in one go, because I use film and am not always completely sure of what I have photographed before. It has happened that I had pairs without realizing it, so there is an element of post-production. But when I photograph I know that this is one of the ways I will present my work. And presenting the work, bringing it to a wall or into a book is again a very interesting and distinct aspect of photography.

tm: So when architects came to you with a commission, are they employing you to represent their architecture from your point of view or would they tell you what they would like to have captured?

hb: Generally most architects will not say what they want to have captured. I will ask them about early concepts or sketches to get an idea about the origin of a work. In some cases architects really want a photographic essay in which I am given free rein, can pair images or be very abstract. This is of course a condition I feel very comfortable with. Not every commission is like this, though. There can be a more prosaic aspect to my profession.

What I should bring out of a building - can be established in dialogue, but I also need to understand the sensibility of an architect.

tm: Your photographs are very atmospheric and one could even say personal, whereas your list of clients consist mostly of the big names which have the tendency to cover most architectural styles. How do you choose your clients?

hb: Well, you could say that my work and the majority of clients have something in common. There is an exception, Zaha. She is not like Zumthor or Caruso St. John; she has a different style. I am not a critic and I don't stand for this or that style. There are things that lie closer to my sensibility than others, but I am full of admiration and absolutely like the work of Zaha Hadid. I enjoy photographing her architecture and like the position she gives me as a photographer. She is interested in the way I record the building- process, when I really go into the essence of the building, and remain very abstract. There is something fascinating about framing her work, the sense of endlessness, that there is no boundary between a wall, the floor or a door—it is just one. And that's a completely different challenge to framing a building by Peter Zumthor. For me it is important to be able to play both ways.

I like to work with light and materials. If a project doesn't have beautiful materials where, when you get closer they just get richer and richer, I have to compensate by bringing in a lot of dynamic. I like it when the sunlight enters the building and changes it completely during the day. Again if this doesn't happen you have to compensate with something else. The use of light and capturing details in material are the most natural ways for me to express the qualities of a space.

If you want to give shape to what you are photographing you have got to be aware of the light that surrounds it. To work with light you have to be very patient. It requires a lot of time and returning to several positions in different settings. The light might be good now, but is it also good on the façade? So one day you have to be here and the next there. I always say it's like dressing the building. You might want to give it a very beautiful dress or a simple coat. The appearance changes with different lighting. It doesn't mean that one suits it more than another, but expresses different aspects of a building. I find it magical to be in a place from early in the morning till evening and to look at all the changes and moods. I was in Belgium photographing for Van Duysen last week. The land was very flat and the sun low, and it just threw the last rays onto the setting and then was suddenly just gone. It's wonderful; it's like a performance that you are playing with.

tm: And you want to be in many different places at the same time.

hb: You have to organize yourself, yes. And make sure the next day is sunny again (laughs).

tm: How long does it take you to photograph one building?

hb: Let's say the maximum I would take a day is 25 shots. For each shot I want to be sure that it is the one I want. Film is expensive, it is heavy and you have to prepare it. You can't have an endless amount of it for one day. Sometimes it is very quick and sometimes you have to keep going back.

tm: Do you take the same picture twice just in case the first doesn't work out?

hb: I always do two. I have a film-holder that has one on each side. It is too much of a risk to just take one. Often if one situation is nice I might play around and do a variation of it.

tm: It seems like a difficult task to photograph something that is often so large and

that has taken so long to build.

hb: Exactly! And to think this architect has spent 5 years of his life and I might spend a week (laughs). You have to enter their world, and also hope that the architecture is also willing to open up.

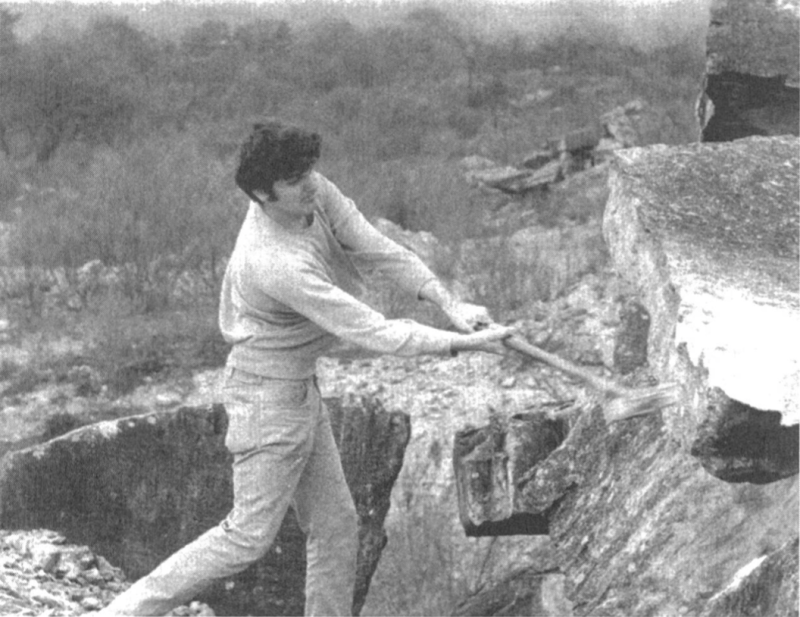

tm: A lot of your work is done during the construction stages of a building. Where does this interest in documenting the building process come from?

hb: I think that some architects build in a way that is very interesting. Zaha's casting is fantastic! She <has> to show it and I <have> to be there when they do the moulding and casting, and when they reveal those pure forms. Other buildings might be beautiful but they are just not interesting while being built. I like the building site. Perhaps this goes back to the idea of a ruin or a historic building, it's not yet there so there's more freedom. It is a gesture and you can go straight to the point.

tm: You studied in Rome, a city surrounded by a vast amount of historic buildings. Architects seem to have a fetish for ruins, is that something you share?

hb: When you take a photo of a building you create something that will not exist in that form any more soon after. It becomes a ruin because it is such a specific moment that you capture and that will undergo change due to the course of time. At the moment I am interested in traces—to look at the ground. You can see the traces of human activity. It doesn't matter if it is a factory building or the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. It is the trace that interests me, so I photograph what I find. If you take a photograph you can assume you have a concept, that you are looking for something.

I grew up in the baroque city of Rome. The Roman ruins aren't part of your daily life, apart from the Pantheon which is part of the city's texture. I do like to work on historic buildings, it's almost refreshing in the sense that they are just there; they're part of our history. I can play with it without being anxious about disturbing the image of the architect.

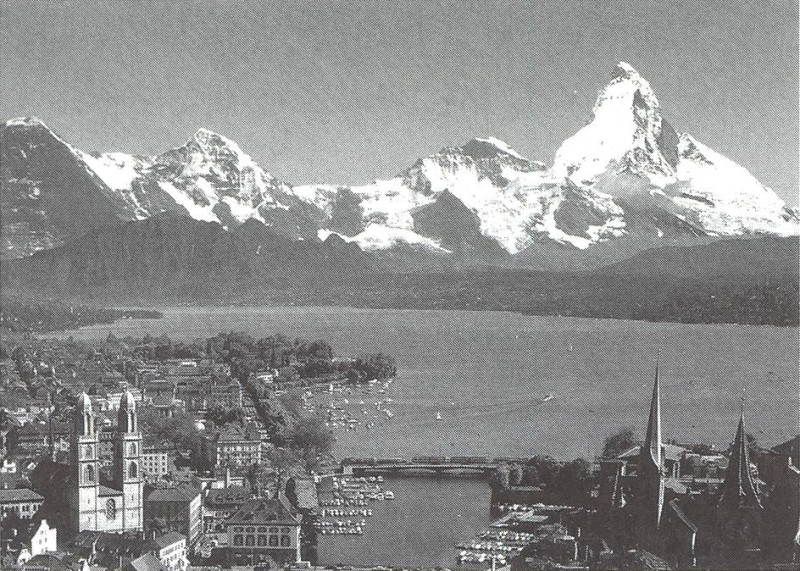

tm: Do your interests lie purely in architecture photography?

hb: I really enjoy photographing landscape. For me it is still space; it is space with a different scale. My previous essays had to do with the making of this space. About the geological formations and the types of stone, the glaciers, the way they crack and create lines. The essay I shot in Switzerland called »Paysages» was about the walk and the diagonal in landscape. To me the landscape is always a walk, it is not a point I go to, to see a panorama. It is the same in architectural details—the relationship of unfolding and lines. I am doing a project in the Atacama Desert about the formation of fog. One place I visited had its last 6mm of rain in '92. There is a fog that doesn't break into rain. The inhabitants have been building screens called <fog catchers» which are pieces of sheets that can collect this water. In that case it's about the relationship between the land, the fog, and the need of water. Landscapes are difficult because they are very beautiful. You have to be disciplined to stay focussed on whatever you want to explore.

tm: You have a distinct way of revealing the gestures in both architecture and landscape, enhancing their performative nature. While in architecture it seems easier to express this gesture, in landscape...

hb:...you have to extract it somewhat more. We are used to landscapes and don't consider their formation. In the exhibition I did for Mendrisio, which is now at the Bauhaus, there is a dialogue between one architect and another architect or an architect and a place. In one example I paired Zaha Hadid and a landscape. I put a relationship between the forming of a landscape and the formation of the world.

tm: A lot of your photos are black and white.

hb: My personal work, yes. The commission for the museum in Faarborg in Denmark had to be in colour because it would have been a shame not to show the colour. But for my personal work, in which I try to capture moments in which you can create this mental space, black and white helps me to abstract. I think depth has an interesting connection with the different greys; you can choose which point should be really black and which point has light.

tm: How do you withstand digital photography in a time where everything is digital?

hb: You immediately have to tell a client that time is different in analog photography. Nothing is immediate and people are not used to that anymore. Personally I don't have to resist it, apart from my back that occasionally gives me complaints, (laughs)—it get's a little bit heavy. But I have no fascination for all of these possibilities. I think limitation can be more creative than having countless possibilities. I do not enjoy being behind a computer. If I spend more hours shooting and take fewer images I don't spend any time behind the computer. A friend of mine, a photographer, worked on a book on London and photographed for a year and a half and spent three years editing. I'd prefer shooting for two years and to spend 6 months editing. Ifyou take so many photos, editing is like shooting again, because you are in front of the computer and you have to start choosing again. It is important to say <yes> and to accept that you can't change very much. If something is wrong, it becomes part of it, which might give you access to the image. I find contemporary architecture photography a little confusing. All the images are the same. And they all look very clean and perfect. You don't know if they are photoshopped or renderings. I know some photographers shoot the room and then the people and then stitch them together. Rather do a rendering you know. There are wonderful artists using collage and digital images, but they use them in a real way. Digital photography doesn't convince me if it is merely to make life slightly easier.

tm: Your photographs are so specific and abstract, do you have to convince a client not to show the whole building?

hb: You can't control everything. Now everybody has a camera, everybody makes images and everybody has networks and electronic platforms to share these images. Every space

is <seen>, regardless of bad or good lighting. The architect cannot control his image anymore. In the end he is going to look for a statement, a point of view, details, and a piece of work. It gives me freedom. There are already so many images uploaded onto various networks that I can do my work regardless of that. If someone chooses to work with me they will do so because because I do a certain type of photography, and if not then they will choose someone else. The difficulty comes when they want these abstract photographs and the building is not abstract. (laughs)

HÉLÈNE BINET

Hélène Binet, bom 1959, in Sorengo, Ticino, and is of both Swiss and French background. She currently lives in London with her husband Raoul Bunschoten. She studied photography at the Instituto Europeo di Design in Rome, where she grew up, and soon developed an interest in architetural photography.

NOTES

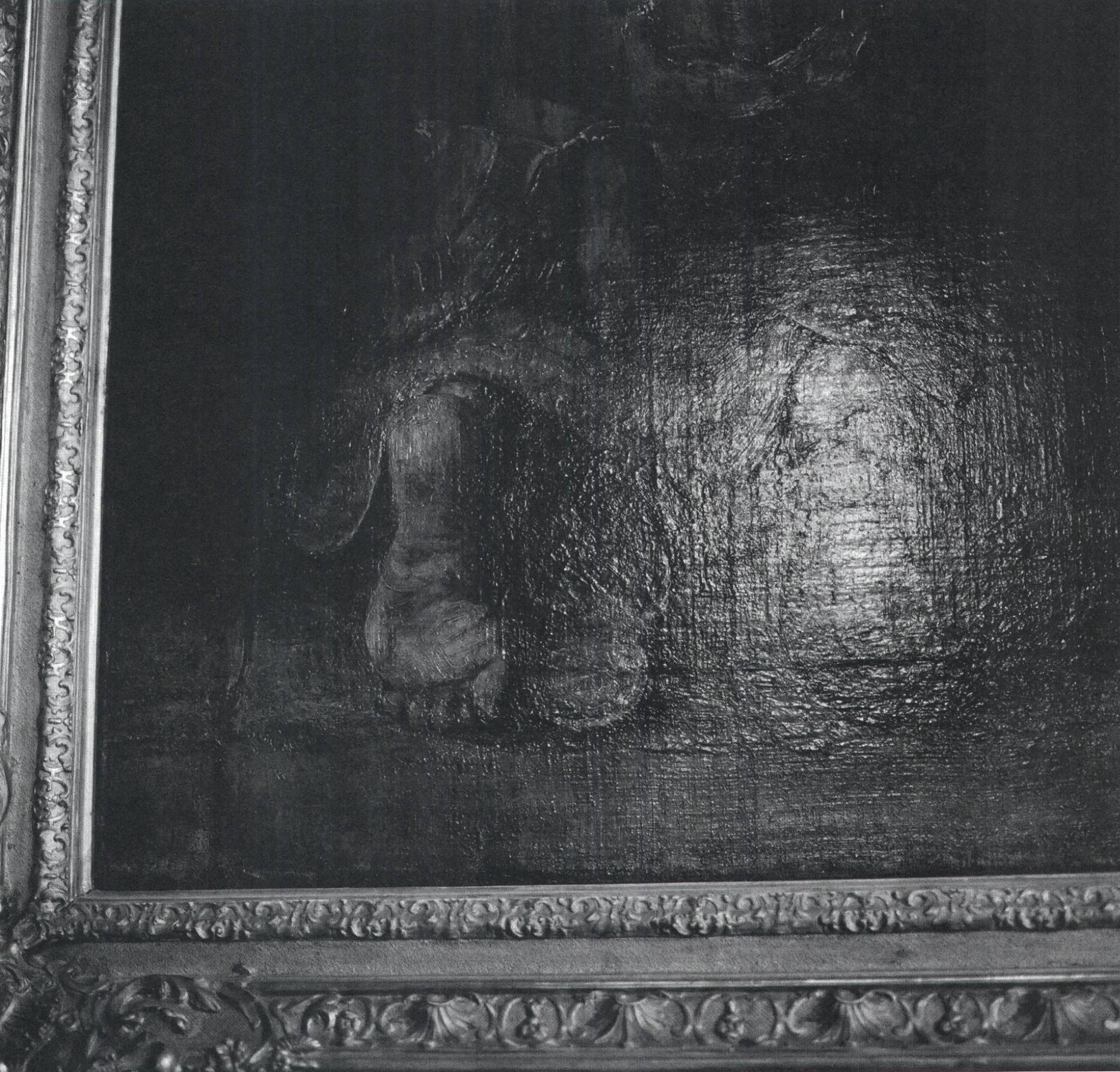

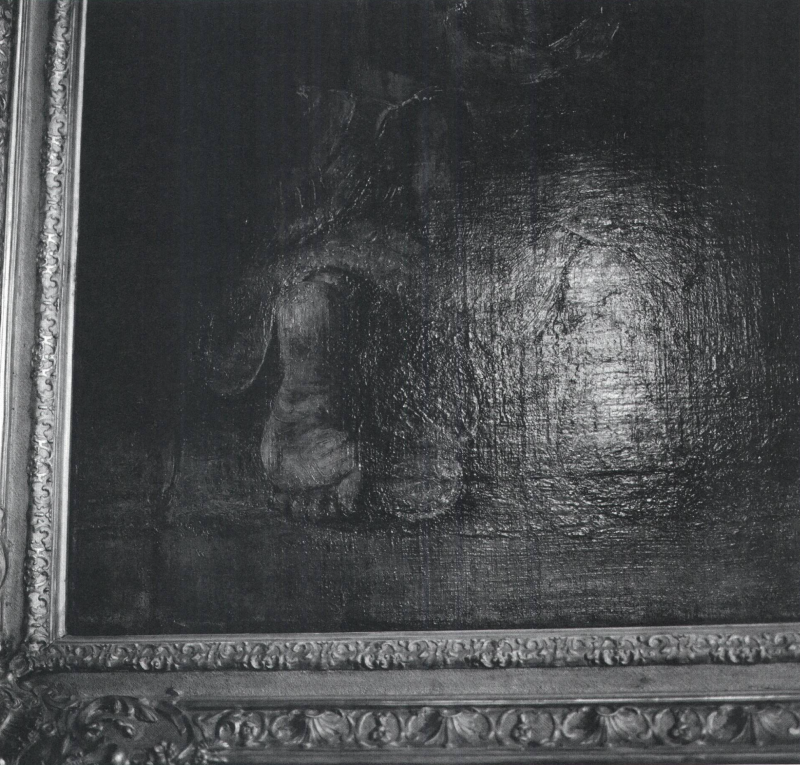

image 001: Detail of Rembrandt's painting in the Hermitage, St Petersburg, June 2015.

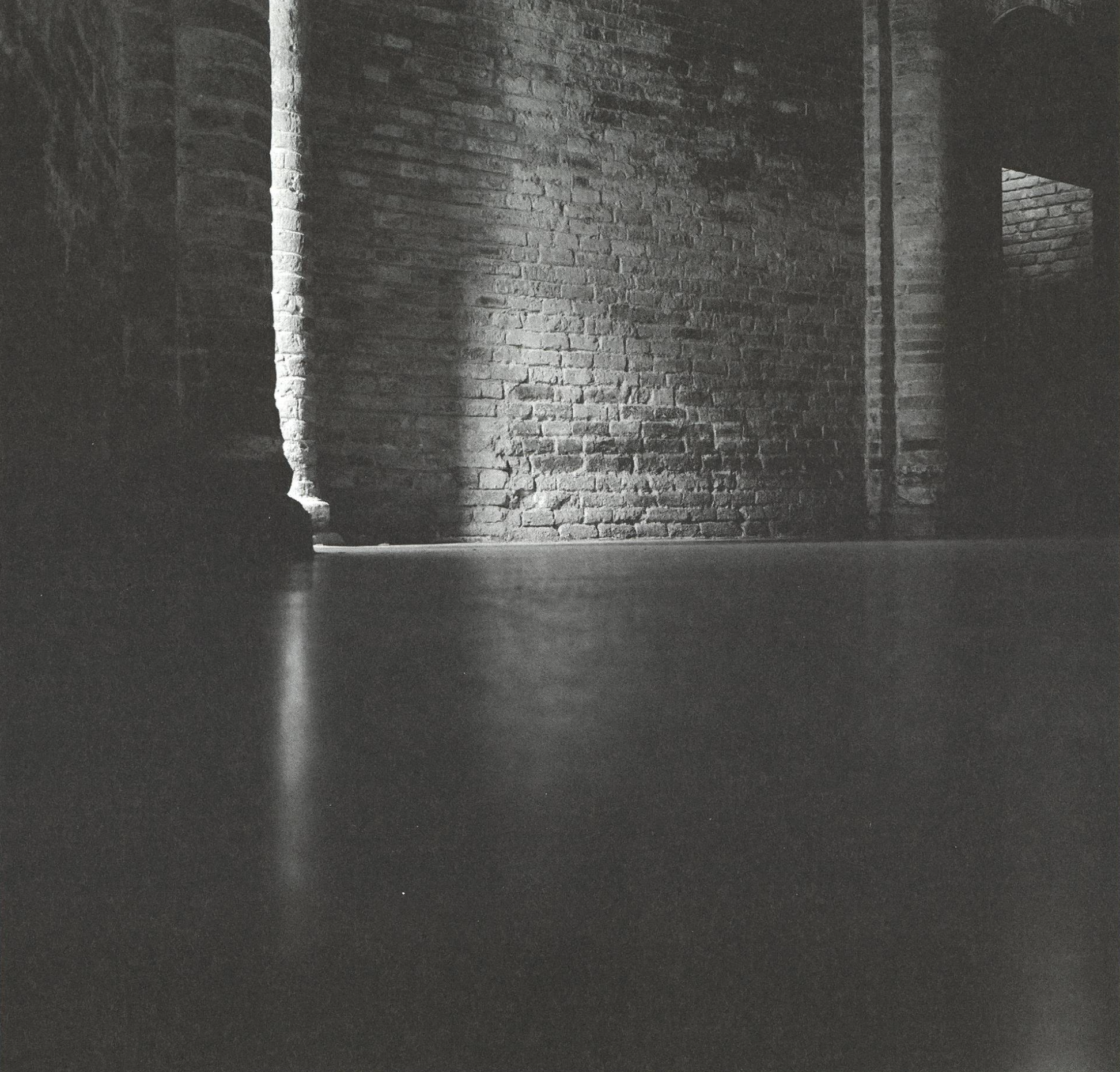

image 002: Abbazia di Santo Stefano, Bologna, April 2015.

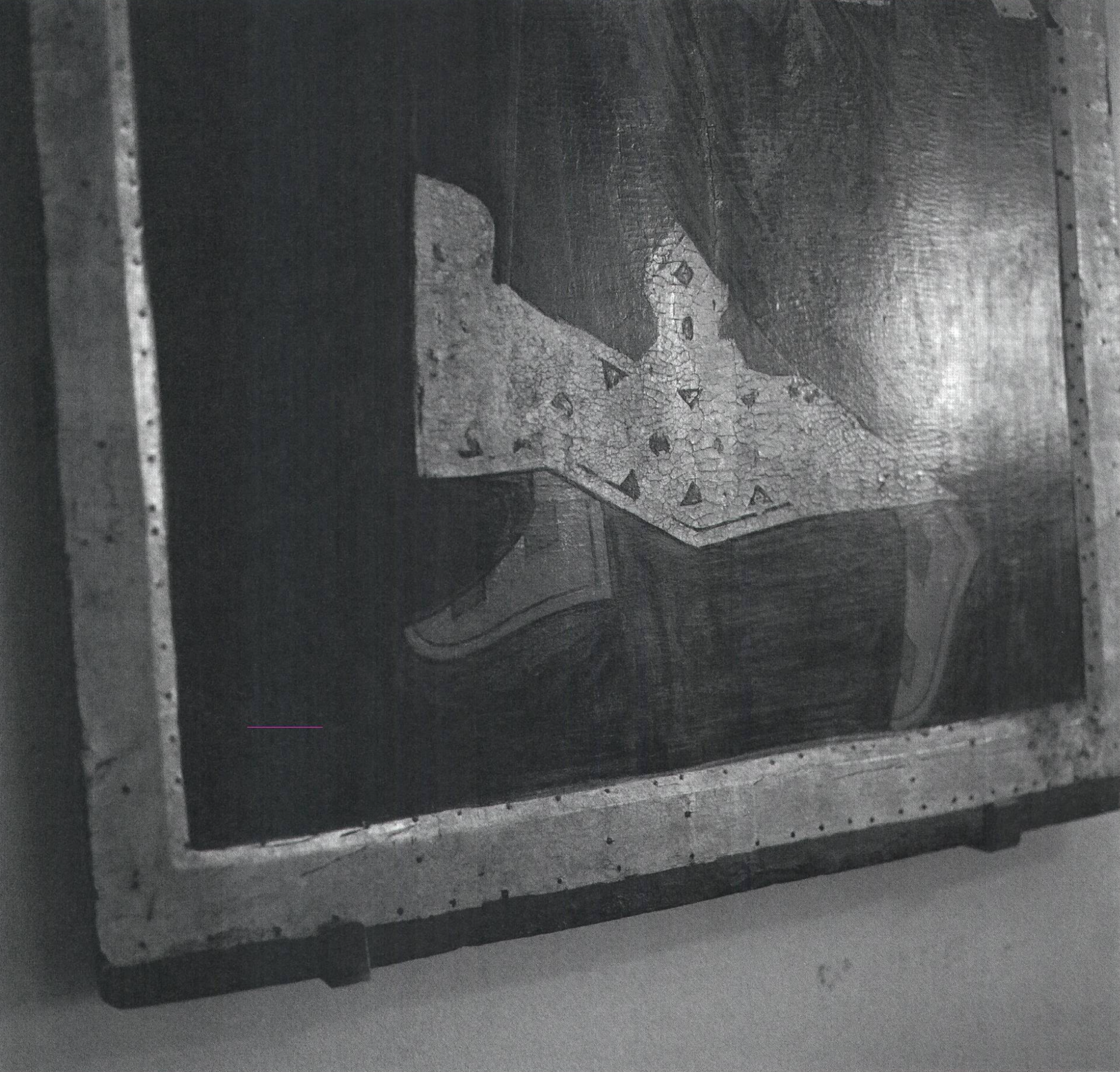

image 003: Detail of painting in The Russian Museum, St Petersburg, June 2015.

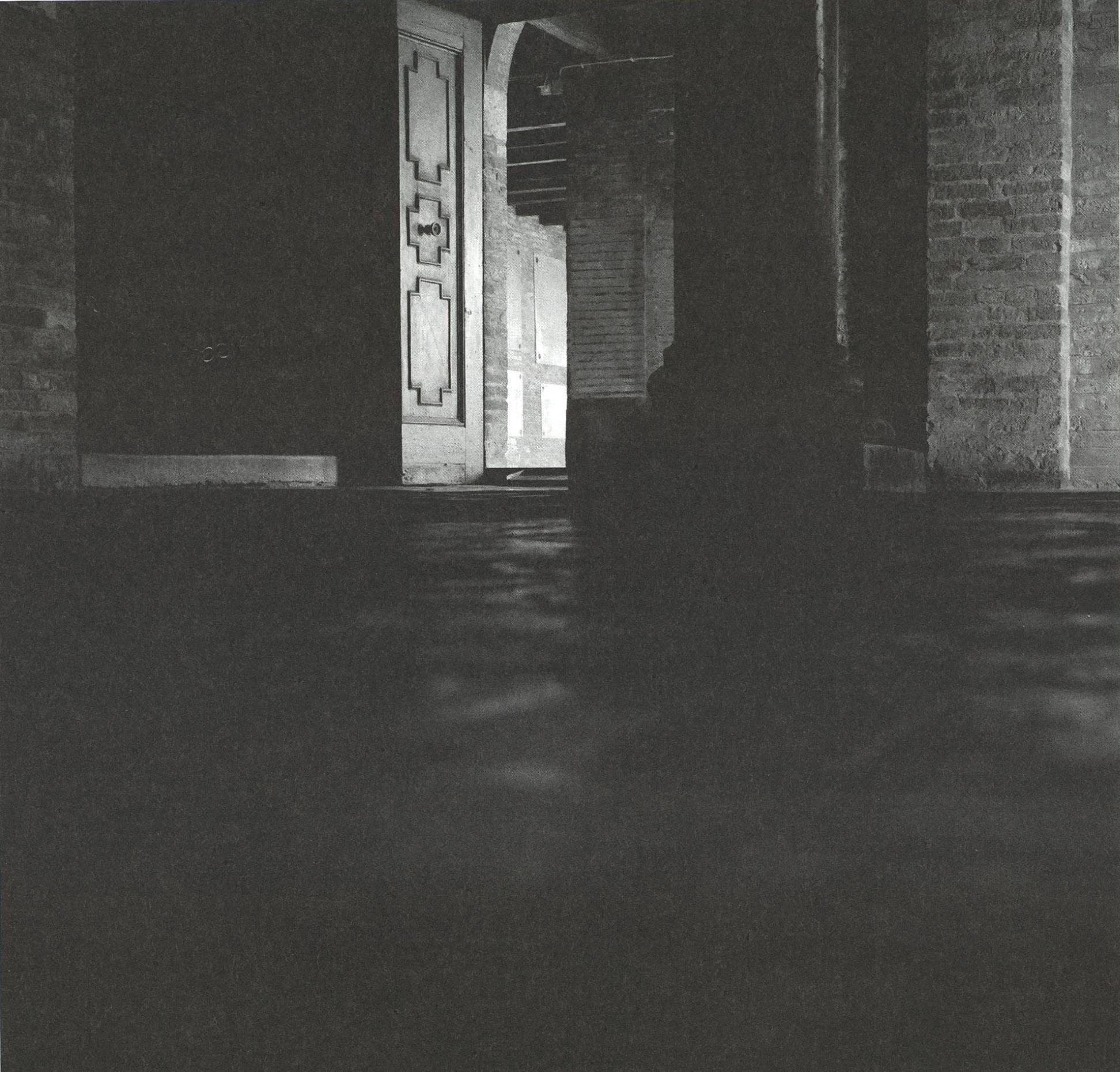

image 004: St. Lebuinus Church, Deventer, July 2015.

image 005: Detail of painting from Palazzo dell'Archiginnasio, Bologna, April 2015.

image 006: Abbazia di Santo Stefano, Bologna, April 2015.

image 007: Abbazia di Santo Stefano, Bologna, April 2015.