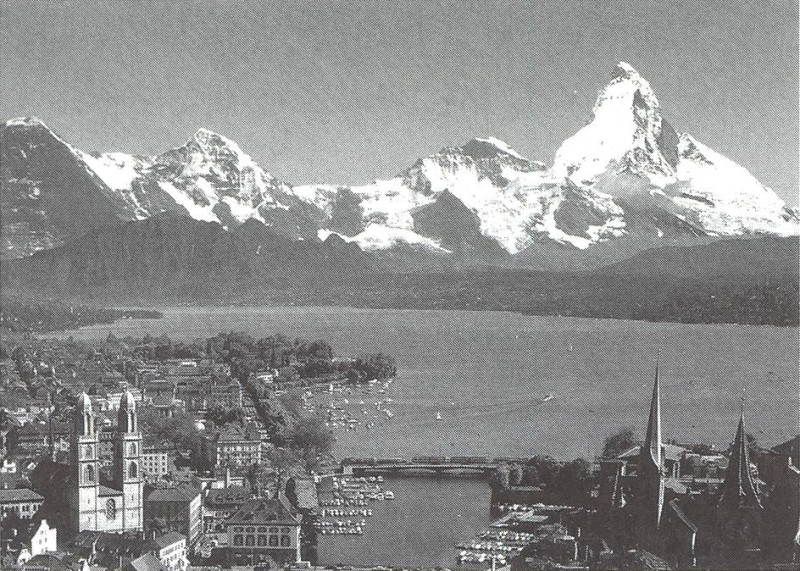

The recent fall of part of the Matterhorn this summer made the front page of all the local newspapers of Switzerland. The emotional upheaval brought about by this event does not seem lodged in a new ecological consciousness (who has since stopped using his car?) but rather manifests a shaking of the Helvetic imagination. Additionally, this landslide exposes as well the fragility of the mountains, usually perceived as immutable and eternal, as it puts into question one of the pillars of Swiss identity. Although half-Italian, the Matterhorn had become the symbol of Switzerland. Its almost obsessive presence - from the packaging of the chocolate Toblerone to the last advertising campaign of the pencils by Caran d'Ache - attests to the emblematic status of the Matterhorn.

The mountain represents much more than a mere geological phenomenon. Moreover, it provides a veritable screen on which all the fantasies of urban society are projected. Formulated for the first time in the 18th century by the «inventors» of the mountains, who incidentally were all from the city, these representations curiously have not changed.(1) In affiliating Switzerland with the mountains, the 18th century does not only create a new identity but gives its reveries a definitive geographical place.(2)

The most recurrent vision of the mountain is the one pertaining to a preserved world. Essentially following from the work of the humanist Albrecht von Haller, the mountain is seen as a terrestrial paradise. In his famous poem published in 1729, ‹die Alpen›, he lauds the probity and the simplicity of the alpine life whereby the morality of the society is associated with the virginity of the landscape.(3) Jean-Jacques Rousseau amplifies this idea. In his novel, ‹Julie ou la nouvelle Héloïse›, published in 1761, he insists on the moral order generated by the mountain. The Alps protect their inhabitants from the corruption of the city. Switzerland becomes the illustration of his theory on human nature. Louis Sébastien Mercier, who offered a critical overview of the life of Paris just before the French Revolution in ‹Le Tableau de Paris› from 1781-1788, sees also a link between mountains and democracy. Despotism is impossible in Switzerland, he explains, because one just needs to climb the mountains to be above the tyrant.

If the mountain can counter corruption, it can also prevent any kind of disorder. A sojourn in Switzerland is then recommended for the treatment of psychological and physical illnesses such as depression or tuberculosis. The development of natural medicine (A.Rickli) and the progress of bacteriology in the 19th century extend the predilection for an alpine respite. In the following century, the sheer number of sanatoriums built gives Switzerland the status of «Kurhaus Europas». This sanitary tourism labels not only the image of the country but also marks the territory. The intake of patients, sometimes very contagious, requires increased measures of hygiene and consequently the establishment of sanitation infrastructure. At the same time, the wealthy tourists expect to find in their hotel a tidiness that corresponds to the purity of the landscape. Limited first to touristic areas, this phenomenon spreads progressively to the rest of the country, making Switzerland the symbol of cleanliness.(4)

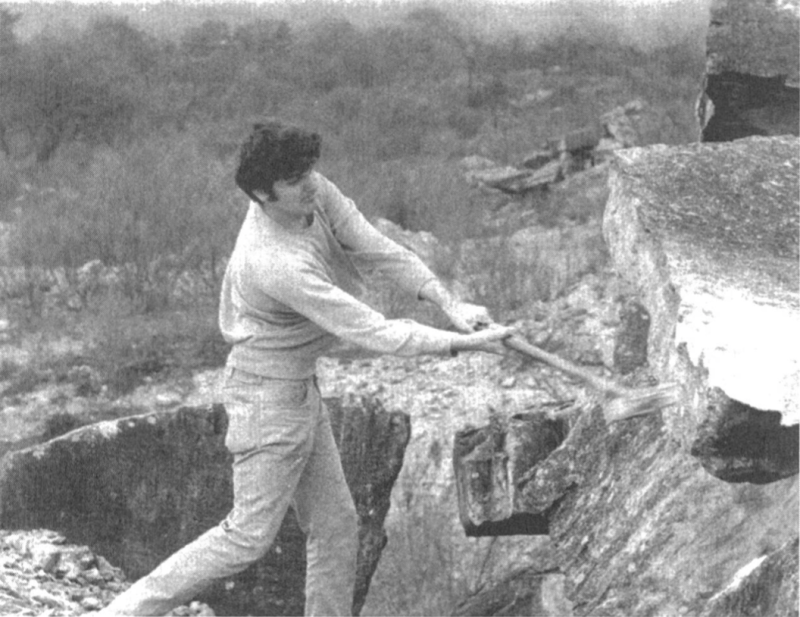

Whereas the drive for domination and conquest characterizes the capitalistic society, the undomesticated landscape of the mountains stands for a challenge. Since the ascension of the Mt Blanc by the geologist HoraceBénédicte de Saussure at the end of the 18th century, mountaineering evolved as one of the favorite sports of the next century. Because it demands temerity, tenacity, and precision, it is the place where one can reveal ones true personality. These qualities are also required by the industrial society.(5) It is not surprising that at the onset of neo-liberalism, winter sports are still in fashion. The audacity of current snowboarders, for example, responds to the intrepidity of the alpinist. This desire for domination finds its full expression in engineering projects of the period. In 1871, Nikiaus Riggenbach invents the rack railway. It is henceforth possible to access the coveted summit without fatigue, as long as one can afford a train ticket. A couple of years later, the tunnel of the St Gotthard is completed. The railway finally triumphs the great barrier of the Alps. By allowing anyone to cross it to his liking, the car further marks the conquest of the mountain. Escalated, slashed, lacerated, and finally penetrated, the mountain is definitively brought under the sway of man.

The high number of publicity campaigns using the mountain to emphasize the national character of their product reveals the tight bond that unites the mountain and the Swiss identity.(6) The first lines of the national hymn «on our mounts, when the sun rises...» serve to ground this identity. As relayed by the historical myths of the Riitli oath or the tale of Wilhelm Tell, this identification happens to be very useful. In a land where everything is divided (language, religion, etc.), the mountain unifies while serving to conceal dissension. By occupying the horizon, the mountain in the same way incites a retreat back into oneself. This is clearly evident in the position of Switzerland relative to the European Community.

The permanence of such images shows that the relationship to nature has not been modified since the 18th century. At that time, the beginning of industrialization modified the environment and thereby was established a new relation to nature.(7) This transition is illustrated perfectly by the invention of the mountain. The shift did not happen only on an aesthetic level one prefers now «wild» landscapes to orderly countryside but also on a philosophical one. The «natural» nature is viewed as virtuous rather than ferocious. It modified consequently the relation to the city. If the opposition nature/city by which both are defined is still valid, the terms have been nonetheless inverted. The status of the city changed: from being the sign of culture, it became the place of lewdness. On the other hand, the mountain understood previously as the dwelling place of monsters acquired maternal qualities: it nurses, harbors, and protects. The mountain, however, is not associated with the mother per se. Rather, its immaculate summit confers on it a virginal character, as expressed, for example, in the name Jungfrau (virgin). As such, it arouses the notion of male cupidity. The mountain is a land to deflower. The erection of bridges, the incision of railways and roads, or the drilling of tunnels can be interpreted as so many different ways of taming nature.(8)

This conception of nature curtails not only our relation to the environment but also to urbanism. Although it currently forms a «nébuleuse urbaine», to quote the historian of urbanism André Corboz, the city is still defined in the collective Western imagination in opposition to nature. This dualism generates a simplistic vision of the world by reducing everything to binomial categories. If the ensuing hierarchical classifications such as man/woman, center/periphery, wealthy/poor, etc. are perfectly suited for a neo-liberal system, these classifications are insufficient for apprehending the complexity of the world. By unsettling the myth of the mountain and as a result, the identity of Switzerland, which must both be understood as inventions of the industrial age, the landslide of the Matterhorn forces us to imagine a new way to relate to the world. Furthermore, this geological event might even announce the end of capitalism...

ANNE VONÈCHE

Anne Vonèche is an art historian and worked as an assistant at the Chair for Landscape Architecture and Landscape, ETH Zurich.

NOTES

(1) The discovery of the mountain as a landscape illustrates the theory of A. Roger. He conjectures that the landscape can only be perceived through the media of art. Before its mediatization in the 18th century, the mountain, when it was seen, was considered like a wart of the landscape. People thought that they were actually the refuge of monsters. (On this subject, see A. Roger, Court traité du paysage, Paris (Gallimard) 1997)

(2) Switzerland is maybe the only case where Utopia becomes a topos!

(3) This poem was translated into almost every language and several times republished (F.Walter, Les Suisses et l'environnement, Genève (Zoé), 1990, p. 40)

(4) G. Heller, „propre en ordre", Lausanne (éd. d'en bas) 1979, pp. 120-140

(5) L. Tissot, Naissance d'une industrie touristique, Lausanne (Payot) 2000, p. 49

(6) In its last advertising campaign, the Swiss office of tourism even brands the mountains as a national invention, applying a copyright on them.

(7) J. Starobinsky, L'invention de la liberté, Genève (Skira) 1964

(8) Curiously in Summerian writing, the combination of the pictogram of a

woman with that of the mountain denotes slave. (J.L. Calvet, Histoire de l'écriture, Paris (Pion) 1996, p. 51)