«Respect the ‹Naturlangsamkeit› which hardens the ruby in

a million years, and works in duration in which Alps and Andes come and go like rainbows.» Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1841 (1)

It was in a treeless and formless tabula rasa in which the Brasília Palace Hotel was constructed in 1958. Together with a chapel, and the president’s residence, the hotel was one of the first permanent buildings in Brazil’s new capital. They were early samples to showcase Oscar Niemeyer’s architecture and

a testing laboratory for the construction of the city set for inau- guration two years later.

Whilst not mentioned anywhere in the project’s description, two «Ficus elastica» trees were planted next to the Brasília Palace Hotel. Originally from Southern Asia, the trees were as foreign to the environment as the modernist building. As young seedlings, they were barely noticeable in the first photographs of the widely publicized hotel (A).

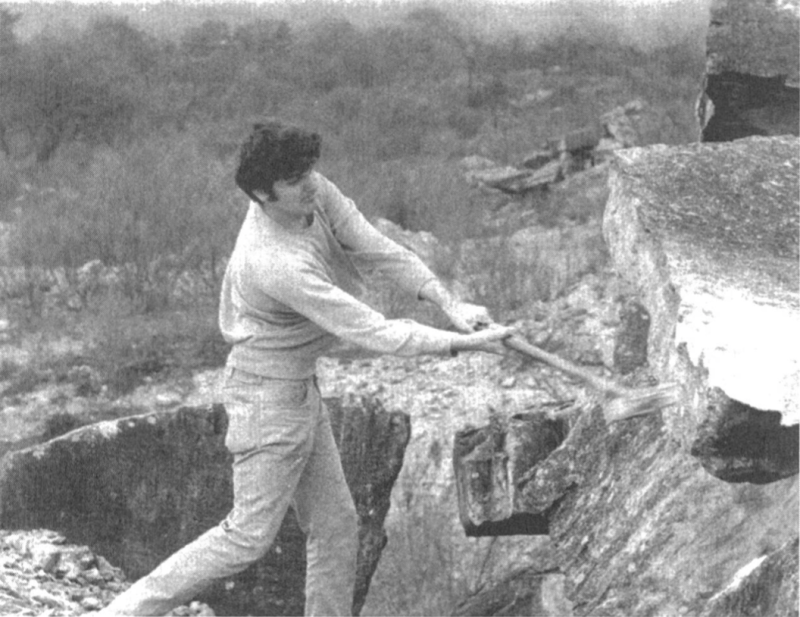

Brasília was an architectural wonder designed from scratch to be built in just three years. The «city of the future» was the symbol of a larger modernization plan to colonize Brazil’s central plateau, seizing what was presumed to be empty land. The environmen- tal erasure was not only symbolic but also physical. In just a few hours in 1957, hundreds of bulldozers, assigned to carve the delicate lines of Lucio Costa’s urban plan to the ground, destroyed millions of years of evolution of the tropical savannah known as «Cerrado.» Heavy machinery performing colossal earthworks and massive clearings substituted trees and high grasslands for large patches of red dust (B).

Raised on «pilotis», the architecture of the Brasília Palace Hotel avoided physical contact with the devastated land. Its photo-graphic representation reinforced this hovering-above-the-ground impression. When captured on film the columns painted black tended to disappear under the building’s shadow, while the volumes’ white geometrical forms tended to be highlighted. This indifference to the immediate context translated the larger con-ceptual dualities that Brasília’s project was based on: civilization vs wilderness, order vs disorder, and architecture vs nature. At that moment, forests and trees were considered physical barriers to Brazil’s modernization and its territorial reorganization led by the State. To take possession of the interior of the coun- try, several roads irradiating from the new capital were simulta- neously constructed. As the road building activity reached the Amazon Forest, commonly referred to as an impenetrable «Green Hell», thousands of workers and machines painfully advanced through the dense vegetation by cutting down enormous trees. Aerial photographs of a straight line in the forest made visible and acceptable the «conquest of the Amazônia», celebrating the triumph with captions such as «Each falling tree is greeted with shouts of joy.» (2)

In the context in which deforestation was being praised, Lucio Costa aspired Brasília to become greener. For him, rather than an inhospitable desert, Brasília should always have appeared as described in his urban plan, a garden city. Fourteen years after Brasília’s inauguration, the city was still not green enough for its main inventor, a condition that was difficult to achieve due to vegetation’s slow growth over time. In 1974, Costa presented a list of suggestions in which he persistently concluded with the following: «Plant trees, plant trees, PLANT TREES.» (3) Paradoxi-cally, when confronted with landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx’s proposal to provide pedestrians with more shade from trees in a central part of Brasília, Lucio Costa advised «[…] it looks very nice [the trees], but I don't agree […] I would prefer it to be an open area so that we can see the architectural vol-umes.» (4) For him, vegetation, although necessary, should always be banned to the background of architecture.

Unnoticed throughout the building’s lifespan, which included a major fire in 1978 and its abandonment for many years, the barely visible trees of the Brasília Palace Hotel slowly turned into central figures. When the hotel re-opened in 2005, completely revamped by 98-year-old Oscar Niemeyer himself, architecture was now banished to the background.

Roughly sharing the same age as the building, the two tropical plants sprung up in defiance of the customary representation of architectural modernism. Their overwhelming spatial presence, impossible to be edited out, destabilizes, and confronts the time-less and autonomous image of modernist architecture. The trees, as elements that record time with their monumental growth, attest that buildings are not static, and are part of history (C).

Today, the enormous «Ficus elastica» host more guests and spe-cies than the hotel’s 180 rooms could ever imagine. While daily maintenance keeps the trees’ branches and roots un- der control (D), it seems inevitable that, over time, they will physi-cally engulf the building itself through any crack they encounter (E).

Days before the inauguration of Brasília, the French art historian Germain Bazin, while walking around Niemeyer’s recently completed palaces, declared: «This is too beautiful, but it won’t last.» (5) Was he doubting the material quality of the construction? Or the political fragility of a young democracy? Or perhaps he meant that, next to «Naturlangsamkeit», Brasília is a split second.

CIRO MIGUEL

Ciro Miguel is a Brazilian architect, photographer, and doctoral fellow of the Institute for History and Theory of Architecture at ETH Zurich. His research revolves around alternative narratives to the built environment through photography. He holds a professional diploma from the University of São Paulo FAU USP and a master’s degree from Columbia University GSAPP. Ciro Miguel was co-curator of «Todo dia/Everyday», the 12th International Architecture Biennale of São Paulo (2019), and co-editor of the book «Everyday Matters: Contemporary Approaches to Architecture» (Berlin, 2021).

NOTES

(1) Ralph Waldo Emerson, «Friendship», in: Essays and Poems, New York 2004, p. 218.

(2) Murilo Melo and Jáder Neves, «Brasília-Acre: A Estrada do Pacífico», Manchete 428 (1960), p. 12.

(3) Lucio Costa, «Brasília é um Milagre», Manchete 1167 (1974), p. 28.

(4) Marianna Gomes Pimentel Cardoso, «A obra de Roberto Burle Marx em Brasília: O papel do paisagista moderno na capital mod-ernista», in: Elane Ribeiro Peixoto et al. (eds.), Tempos e Escalas da Cidade e do Urbanismo, Brasília 2014, https://shcu2014.com. br/discurso%20profissional/305.html (accessed 3 February 2023).